To read The Third Plate is not only to take an extraordinary journey in the company of chef and writer Dan Barber. It is to be a guest at the birth of a brilliant and important idea.

His travels, investigations, reading and thinking go beyond an exploration of what ails our food systems – and the critical importance of restoring soil health and protecting what remains of fish stocks and marine life. Dan Barber goes back to the beginning… the seed.

The first book: The Third Plate

Accompanying Dan as he comes to appreciate the seed as the beginning of the recipe, and the vast and imaginative potential of what could happen if seeds are bred for flavour and for place, is a revelation.

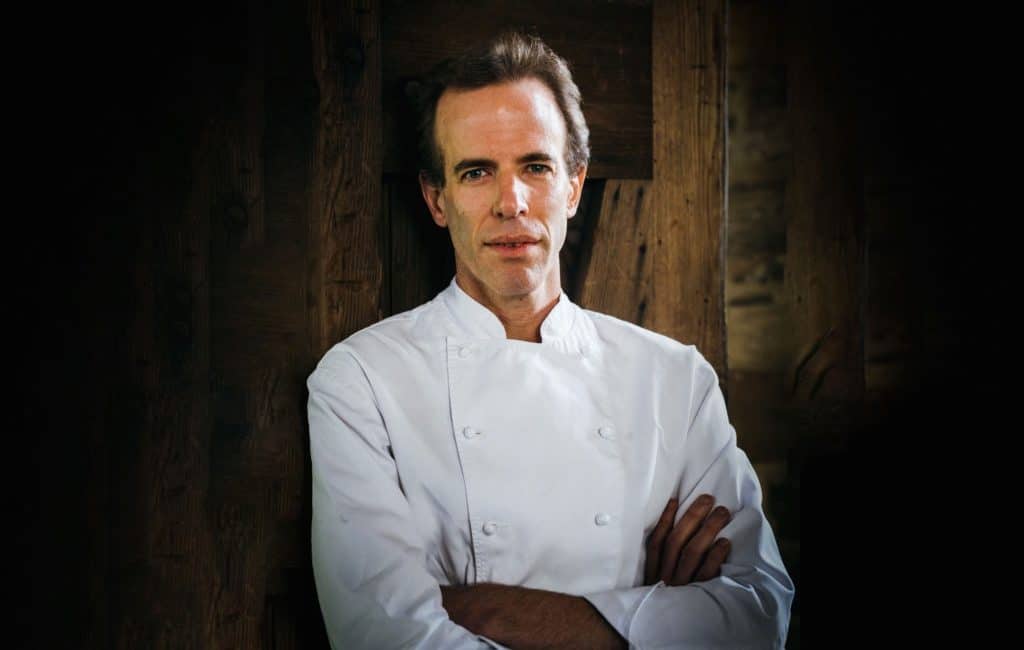

As executive chef and co-founder of award-winning, critic-wowing and public-revering Blue Hill at Stone Barns and sister restaurant Blue Hill in Manhattan, New York, Dan acknowledges what it is to have influence: “I don’t quite understand it – it’s crazy – but I do recognise the broadcasting, trendsetting and cultural influence that chefs have.”

With Row 7 Founders: Matthew Goldfarb and Michael Mazourek (Pic: Johnny Autry)

We chatted to the ‘merchant of happiness’ and now co-founder of Row 7 Seed Company about the power of cooking, fixing our broken food system, how to create recipes for the future before the produce is harvested – and why the cucumber lost its flavour.

In a world obsessed by influencers, we would be fortunate if all those who command attention used their power as wisely.

“I feel so fortunate to be a chef” (Pic: Jade Nina Sarkhel)

Dan Barber:

I recognise the power of the chef in today’s world. The fact that I can create a dish and several years later have an ingredient reverberate into the mainstream food market is weird, but it’s kind of cool.

Am I a chef or an activist? As 99% of my day is spent behind a stove, I wouldn’t call myself an activist. But there is something serendipitous about my work that I get to by accident – the opportunity advocate for ideas.

To coalesce around the pursuit of good flavour is to use the world in the right way… in terms of how we grow food. Not all chefs might describe their work with the same objective as me, but we are united under this drive for delicious food.

Sustainability tastes delicious (Pic: Jade Nina Sarkhel)

Pleasure and high ideals do not usually go hand in hand – but this movement is all about good cooking, good food and the future of what we want to eat and feed to our children. It’s really about hedonism, pleasure and the connections to these very important ideals and the positive effects on the environment, community and political landscape.

I feel so fortunate to be a chef – I get to be the merchant of happiness. I’m not a doctor telling you to eat more parsnips; I’m not an environmentalist telling you to cut down on meat; I’m not a politician or a healthcare provider; and I’m not your mother! I’m in a pretty great space to inspire someone to risk the journey into better flavour.

Blue Hill Stone Barns (Pic: Ingrid Hofstra)

To illustrate what I mean by ‘the third plate’ I would point to a plate of food – like the one I was serving last night at Blue Hill. It was a parsnip steak – a very large, intensely delicious, nutritious, local root vegetable that has been in the ground for 12 months. We hang it for two weeks, like you would dry age beef, covering it with tallow from Blue Hill Farm’s grass-fed cows. I served it with a side of braised oxtail, an often underused part of the cow, and we carved it at the table like a good sirloin. We made a rich and very delicious sauce with the bones of the meat and served it with cream spinach and potatoes. Using a bit of wit, we served a steak dinner… but from a parsnip.

It flipped the Western idea of what we expect for a plate of food – by putting vegetable or grain at the centre and the meat as a supporting actor. That is idea behind the third plate.

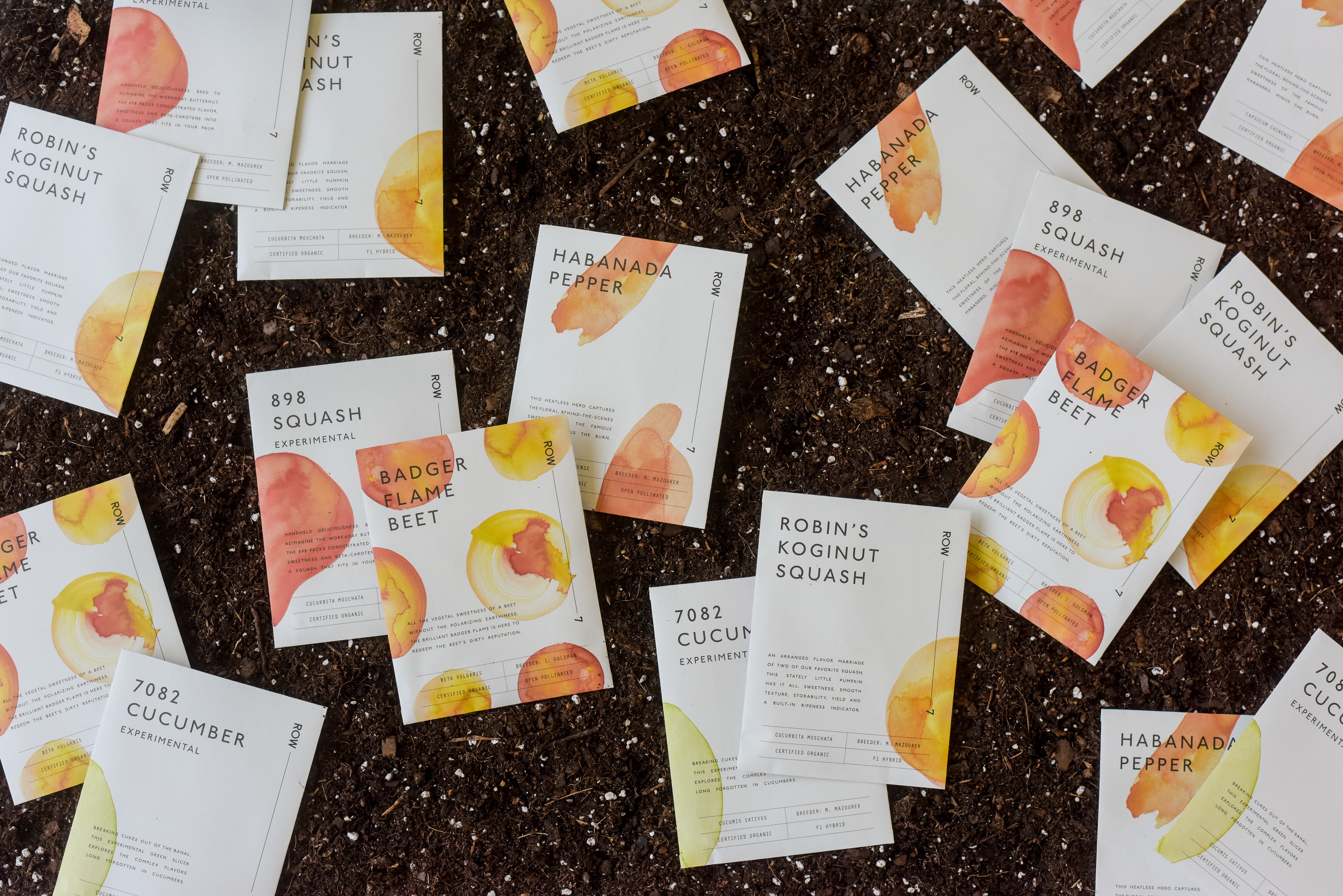

Badger Flame Beet seeds are affordable (Pic: Andre Baranowski)

It’s great if these ideas are able to bleed into mainstream food culture and don’t stay in the cathedral of the white tablecloth restaurant. As long as the ingredients or dish stay somewhat true to themselves, they will end up affecting what people eat in a positive way. I believe that cross pollination of ideas is a legitimate and exciting part of the work that chefs do.

We have the ability to excite people through curation. It’s hard to get people who have become accustomed to a dumbed down version of a parsnip or cauliflower to be introduced to something new if it’s not in the context of pleasure or delight.

“I feel so fortunate to be a chef – I get to be the merchant of happiness.”

I have started carrying around a little black notebook. I’ve just realised that I’m starting to think about writing again. That hasn’t happened since I finished The Third Plate. It took me 10 years to write the book and I carried a notebook that whole time.

You ‘vote’ by cooking and preparing food every day. As Michael Pollan, the great food writer, said – what other political system allows you to vote three times a day?

The power of cooking is big. It’s the best way to activate real change – cooking at home more and cooking with kids. The Stone Barns Center has a great list of ‘30 ways to be a food citizen’. Another one is to try to use meat as a sidecar.

Growing food is an enriching experience, even if you live in the city. If you can put herbs on the windowsill, that’s also really powerful – especially for kids.

Blue Hill Stone Barns (Pic: Ingrid Hofstra)

Can we breed, select and develop a flavour that is at one with the microclimate of a particular location and region? Almost all seeds today are developed in the exact opposite way. They are selected based on statistical analysis of yield and uniformity – not for flavour or disease resistance. As those seeds are expected to perform everywhere – whether the UK, US, China or Mexico – that means dumbing down the genetics.

What if we thought about seeds as specific to place? As citizen scientists we could evaluate seeds and flavours and make decisions about the future of our food based on the specific region. That might not just be ecological, but also tethered to the culture, traditions and history that co-developed with the agriculture of the region.

Traditions and cultural connections should be front and centre – chefs need to curate that part as well.

My new company, Row 7 Seeds, has begun to compile a lot of data. It’s based on creating a community with participatory feedback. The first community is the chef community. We’ve activated 70 chefs around the world to test and evaluate these varieties for gastronomic potential. They will work with a partner farmer also to test and evaluate from an agronomic perspective: do they yield well, do they have good disease resistance, is it a strong plant in that particular ecology?

As cool as the 7082 Cucumber! (Pic: Johnny Autry)

Why is there a cucumber as one of our launch seeds? I became so fascinated with the story of the cucumber. There’s a book just in that!

A Lebanese farmer who I am particularly fond of, Zaid Kurdieh from Norwich Meadows Farm, talked to me about the cucumbers from his childhood that his grandmother used to prepare for lunch and how they perfumed the kitchen. He had some of these seeds and introduced me to them – and it was revelatory.

The cucumber today is the result of what the Dutch did to them. They bred it for sweetness, size and water and so you get none of the complexity of an original cucumber. Until I tasted those heirloom cucumbers I hadn’t realised what they could be or really understood the lack of joy in the modern cucumber.

Modern cucumbers are also a very weak plant. They are susceptible to all kinds of diseases especially fungal diseases – but as the market for organic is very small, the fact that it’s a weak plant doesn’t really matter because you spray the problem away. With organic you can’t do that. So we backtracked to older varieties and married them to newer ones and we released the 7082 cucumber.

The brilliance of it is that it encapsulates the story of Row 7. We are taking something old and modernising it for today’s palette, but also the genetics of the heirloom – the thing that makes it a bit bitter and complex in a very pleasing way – are why it’s so disease resistant.

I’m not exaggerating the power of this cucumber. Not only is the kind of flavour that you or chefs would flip over and that you want to come back to and explore and think about – but it also coincides with the best ecology and the strongest, most nutritious plant.

“Once the seeds are in the ground, the cake is baked.”

Why haven’t we been breeding for those things? I really don’t know but I think we’ll change the market if we keep pushing this in the right way.

I’m in the long game, but we can change a lot in the next ten years. I’ve got skin in the game, so it’s a little unfair to answer this way, but I think that turning to breeders and starting a conversation with the original recipe is what can change things.

Seeds are the blueprint. What came out of the book is the understanding that a lot of this change can’t happen unless you are activating at the seed level. Once the seeds are in the ground, the cake is baked. You can have the best farmer or soil in the world but if you don’t have access to the right kind of genetics they will never be expressed – that’s why I dove so deeply into the seeds.

Row 7 seeds (Pic: Kate Medley)

These seed breeders are so amazing. It’s really ripe in the US for a conversation that could be explosive, especially for chefs.

You could start writing a recipe before the produce ever comes to the kitchen. The idea that you could be in a conversation with a breeder, like I am now every couple of days, is very powerful for a chef to start to think about. That’s why I’ve got 70 chefs in the network – and we’ll increase that and it will run on its own because it’s so self-serving.

Chefs end up looking like better chefs because you cook with vegetables or grains that are revelatory. Your diner looks at you like you have some special power… and the truth is you’ve just begun a recipe where you should begin. That’s the power of this.

My FuturePower would be… to have the ‘super’ palate of some of my hero chefs. Chefs like Alain Ducasse and Michel Rostang seem to have this X-ray-like vision for flavour where they can, upon tasting something, immediately see and understand every element that went into making that bite. It’s really incredible.

Understanding every bite (Pic: Jade Nina Sarkhel)

AtlasQ&A Dan Barber: In the same spirit of collaboration that shines through the acknowledgements section of ‘The Third Plate’, we asked some friends of the Atlas to put their own questions to Dan… from culinary creativity and food fads to a dystopian future soil crisis ► 6 questions for a food FutureHero: Dan Barber

Learn more ► Row 7 Seed Company

8 Agricultural Mavericks podcast ► Dan was talking to Cathy Runciman. Feel the joy as the Atlas co-founder joins Ande Gregson to talk about the power of community and aquaponics v hydroponics.