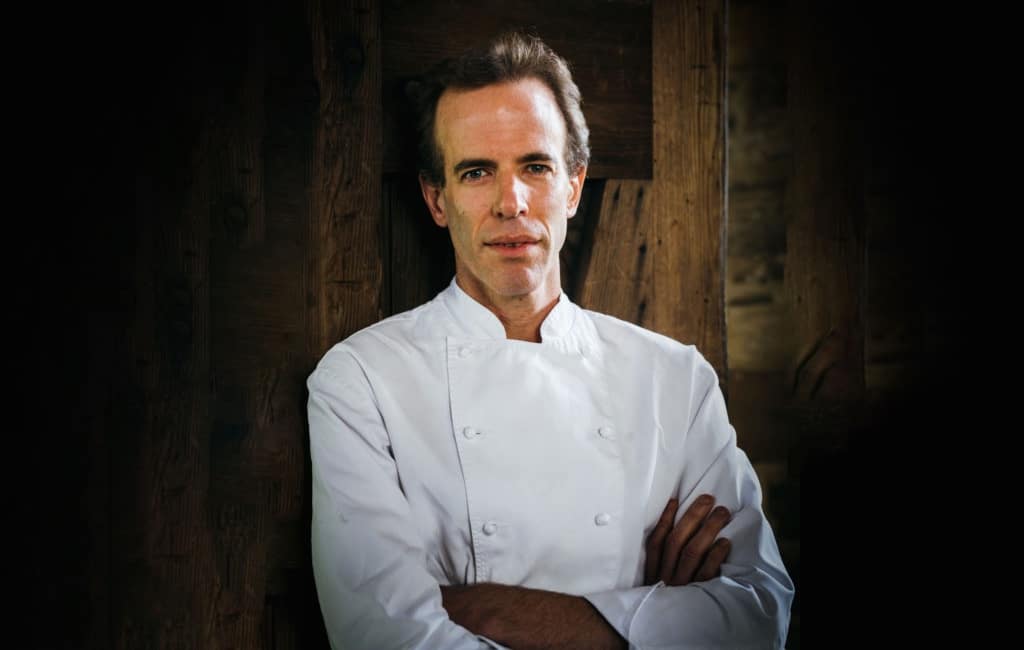

From culinary creativity and food fads to a dystopian future soil crisis, friends of the Atlas ask Dan Barber – Blue Hill chef and co-founder of Row 7 Seed Company – their burning questions…

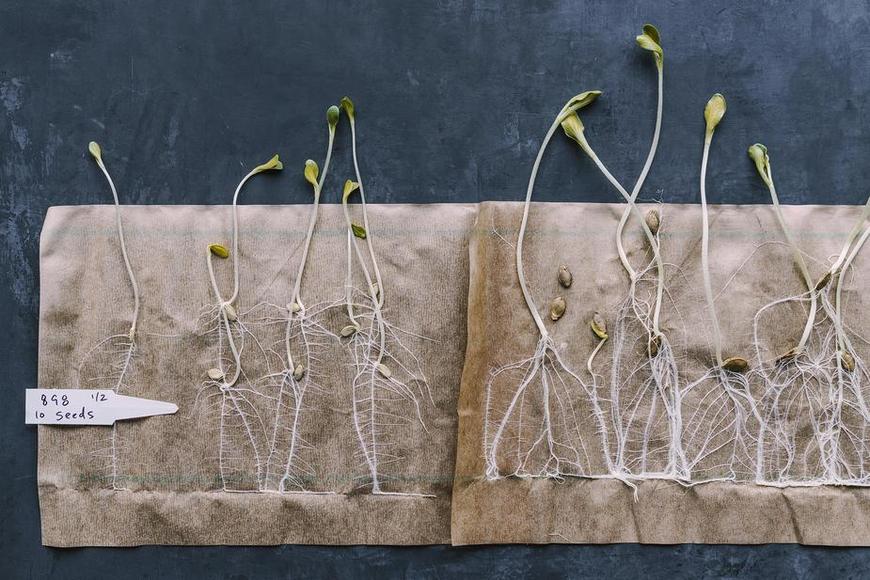

Kale trial (Pic: Johnny Autry)

1. Ande Gregson, founder of GreenLab, an experimental space in London for urban agriculture:

“Is urban agriculture future or fad? Rural farming provides the majority of our food, but how do you see urban agriculture making a real impact in our food systems?”

DB: If you’re talking about aquaponics and hydroponics, then you’re not making me very hungry: I’ve yet to taste anything truly delicious from those systems. In part because it ignores soil. Even forgetting about all the environmental, ecological, open space benefits that a farm landscape provides, the flavour from soil is so far superior. That’s what I’m after and I’m going to stick to it!

The urban hydroponics craze, which is enormous in the US, is being fuelled and funded by tech. They are arguing is that it’s the future of being able to provide food with less bad ecological impact but I just don’t buy that. I see tech doing what tech always does – saying there’s a technological solution to all these problems. But we are talking about biology not technology.

I like the idea that people in an urban area people can have access to and learn about growing food, but I don’t like the idea that all the intellectual and financial capital is flooding to a technological solution to what is essentially a biological problem.

2. Bee Wilson, food writer, historian and author of five books, including First Bite: How We Learn to Eat:

“The line that has stuck with me the most from ‘The Third Plate’ is the one saying that we have ‘lost the taste of wheat’. We don’t know what better quality wheat would taste like, so we don’t know to demand it over white, dusty, agribusiness flour. What would it mean to regain the taste of wheat and how could it happen?”

DB: We should stop growing wheat out of place, and start selecting it for a particular ecology. Wheat is so brilliant, complex, and sensitive. Think about wheat in comparison to other crops like corn or rice. The original corn is teosinte – it’s a wispy grass that we’ve bred and bred into this monstrous crop. Yet if you and I could close our eyes and go back 10,000 years to the middle of a wheat field it would look very similar to how it looks today. That is awesome. What it says is that wheat has lasted in part because it’s so complex but also because it’s so adaptable to different environments. What we should do is take advantage of that – we should celebrate it. That’s the first part.

Then we need to stop turning it all into white flour – because with white flour you’re denuding it of any of its life and its life is where the flavour is. For the whole grain experience, you have to mill it. So you need a milling culture to make the bread, and also a fermenting culture to make use of the waste. In a local wheat economy, there are going to be bad years of wheat harvest so you need to be malting that wheat for beer. This is the community you need.

That’s what I point to in the book and that’s why I get so excited about it. It’s not like a tomato. You and I can go to a field of tomatoes and just slice it and eat it. But you can’t do that with wheat. It has stood the test of time. You understand why it built Western civilization because it forced community. You had to have bakers, millers and processors to come together to create a wheat food system.

So how do you bring back the taste of wheat? One, you bring back the breeders, you bring back the intent of bringing back flavour and two, you bring back a community that expresses that flavour. That’s what so powerful about food, and grains, is that in the right context it forces community. It breaks down walls because you can’t do it without a community of people. That’s an exciting way to activate a new generation of eaters to be engaged with the future of our food.

3. Dougie McMaster, chef and owner of Silo, the UK’s only zero-waste restaurant:

“In a dystopian future where there was little to no fertile soil remaining, what would we eat?”

DB: Ha! Only Doug could ask that! I hope we don’t get to that point. Seriously though, the kind of work that he is doing at Silo, and what he is inspiring, will help ensure that we don’t.

Row 7 mini butternut squash trial (Pic: Johnny Autry)

4. Josep Sucarrats, Editor-in-Chief, Cuina, Catalonia’s most important food magazine:

“Catalan chef Oriol Rovira says that he cannot compete with nature. His work is based on respect for the ingredients which are mostly produced by his brothers on the farm where the restaurant is. Does this respect for natural products hinder culinary creativity or do we need to think about that creativity in a different way?”

DB: I struggle with that: if you work with seed breeders to create a recipe from the ground up, what are you going to add? Don’t you just want to stand out of the way as a chef and express the original intent? Does that call into question the combinations and the jui jitsu stuff that chefs do? I volley back and forth between intense craftsmanship or manipulation of ingredients and at other times – even in the same service with the same vegetable – I slap myself and stand back and allow it to be plated alone.

The modernist movement in Spain was about intensive manipulation to the point of unrecognisable produce and the antithesis of that would be the purity of Alice Waters – buying something perfect and allowing it to be served as is. But I think there is an in between (if that’s not an easy way out!). The craft of cooking is so important to deal with the realities of farming – you often get produce or cuts of meat or lowly grains not in pristine condition and it takes talent and technique to transform that into something that sings. I don’t think I have anything to be ashamed of with that.

I love the vision of Oriol saying I can’t compete with nature. But not to be too cynical, nature – or agriculture – produces a lot of less than perfect stuff. The chef or the home cook can transform that into something exceptional, and that’s something to be proud of.

Sprouted seeds (Pic: Johnny Autry)

5. Louise Ash, Director of Meaning Conference, the leading forum for better business in the UK:

“How can we respond to critics who think that this is an idealised, romantic vision of food production that is not feasible for increased population sizes?”

DB: This idea assumes that the way that the food system is being conducted today will be able to sustain itself into the future – but we have a broken food system. A good proportion of our population is overfed and another is underfed and malnourished. It’s not just inequitable but from a carrying capacity of our resources it won’t last. There is going to be change.

The question is what direction are we going in? Are we putting the pedal to the metal where we genetically modify seeds, increase crop production, increase the effectiveness of interventions such as fertilizers and pesticides, or pump up the investment in growing hydroponically in urban areas to increase salad greens? Or is there an alternative? What I propose, and what a lot of people are proposing, is a smart way to do justice to the wisdom of the past and give it a modern context, and I do believe that it will hold us in good stead for the long game. That is what I am obsessed with.

Upstate Abundance (aka “Trial NY150”) potatoes tasting (Pic: Johnny Autry)

6. Abby Rose, co-producer and co-host of Farmerama, a podcast which shares the voices of smaller scale farmers:

“Soils are in crisis. How can we bring regenerative soil practices to the table?”

DB: My contention is that the best way to do that in America and in Europe is through grain agriculture. 67% of our landscape in the US is in grain and 80-90% of that is in corn and soybean which don’t feed us, they feed our gas tanks and animals. It’s incredibly inefficient but disastrous for soil health because of the kind of rotations and the chemicals needed to support them.

My hope would be to introduce our food culture to a diversity of grains that are soil supporting. Corn and wheat and rice are the major crops that built civilizations – wheat built Western civilizations, corn built Southern civilizations and rice built Asian cultures. We should concentrate not on those big grains, but on the soil supporting grains and leguminous crops – like barley, buckwheat, rye.

In Japan, buckwheat was a rotation crop into rice because it broke up disease cycles and created the fertility for rice. In order to have rice you had to eat buckwheat, so soba noodles became inculcated into Japanese food culture. In the same way that barley into wheat was the rotation in Europe and barley became a major crop, in part because it provided the fertility necessary for wheat – and you got beer and rye. Beans in Southern culture rotate into corn, in North Africa you had millet and in India you had lentils.

These crops are delicious but not celebrated. They should be celebrated more to create a market, so that these rotations become not just environmentally necessary but necessary because there is a real market for them. That is the best way to support a good soil for the future – by concentrating on what’s possible for grains.

The food FutureFixer (Pic: Ingrid Hofstra)

FutureFixer interview: We chat to Dan about the power of cooking, fixing our broken food system, how to create recipes for the future before the produce is harvested – and why the cucumber lost its flavour ► Dan Barber: The chef planting hope

8 Agricultural Mavericks podcast ► Dan was talking to Cathy Runciman. Feel the joy as the Atlas co-founder joins Ande Gregson to talk about the power of community and aquaponics v hydroponics.