United Kingdom (Lincolnshire)

Many children resist new foods, and encouraging them to make healthy choices about what to eat can look like an insurmountable challenge. It’s a challenge that schools struggle with too: in the UK, one in five children start primary school overweight or obese, but by the time they leave this increases to one in three.

The causes of child obesity are complex, but as Jason O’Rourke, Headteacher of Washingborough Academy in Lincoln, UK says: “we are clearly not adding any value in primary school”. Jason, however, sees food education as an opportunity and his school has become a model for a food-based education with the potential to change health and learning outcomes, as well as contributing to more sustainable approaches to how our food is grown and produced.

Where many schools choose to specialise in technology-related topics, Jason realised that food can be a catalyst for learning, because “every child shares an experience of food, whether it’s good or bad”, and that common experience is a fantastic base to start from.

Typically ‘Food Ed’ focuses on the basic skills of food preparation, but when pupils – and often teachers – have had little exposure to a wide range of foods, or have very limited tastes and palates, something else is needed. There is often learned behaviour from outside school to overcome too: generations of people have not had a good experience of food.

The amount of processed and pre-prepared food that children eat is another hurdle. Jason recounts how many children at his school were leaving the chicken drumsticks they were served. When he investigated, he discovered that many had never seen meat on a bone before, having only eaten chicken breast, nuggets or other processed forms. This meant that they approached it like a lollipop, and gave up at licking the bone. The answer: simply teach them to turn it round, and the chicken drumsticks are a firm favourite. “Learning how to eat”, says Jason “is more important than learning how to cook. If you do the first the second comes more naturally.”

Enter TastEd. Based on the Sapere method of sensory education, TastEd is a way to broaden children’s exposure to a wide range of foods, while respecting their individual likes and dislikes. Something that food historian and writer Bee Wilson – author of First Bite: How We Learn to Eat and one of TastEd’s co-founders, recognises as a problem.

“Whatever our age, we tend to eat what we like and we like what we know. So many efforts to get children to eat better fail because there is too much sense of ‘should’ and not enough respect for the role of appetite. We have no hope of changing children’s eating habits for the better unless we can help them to learn new tastes.”

Sapere (meaning to taste and to know in Latin) was developed in France, by scientist Jacques Puisais who created the first ‘taste education’ classes. The method was widely adopted in Finland and Sweden – in Finland, sensory education, is part of all primary school learning – and there is now an international association dedicated to promoting the approach across Europe. Internationally, it reflects and promotes the local culture: in Norway, children are introduced to herring and cloudberries, foods that were being lost. TastEd UK was coached into existence by Stina Algotson, who has been teaching Sapere sensory food education in Sweden for more than 20 years.

Bee tells us: “The two golden rules of TastEd are that no one has to try and no one has to like anything. We have found that saying these words has an almost magical effect on the atmosphere in the room, because suddenly children are free to try new foods with a feeling of freedom rather than duty.”

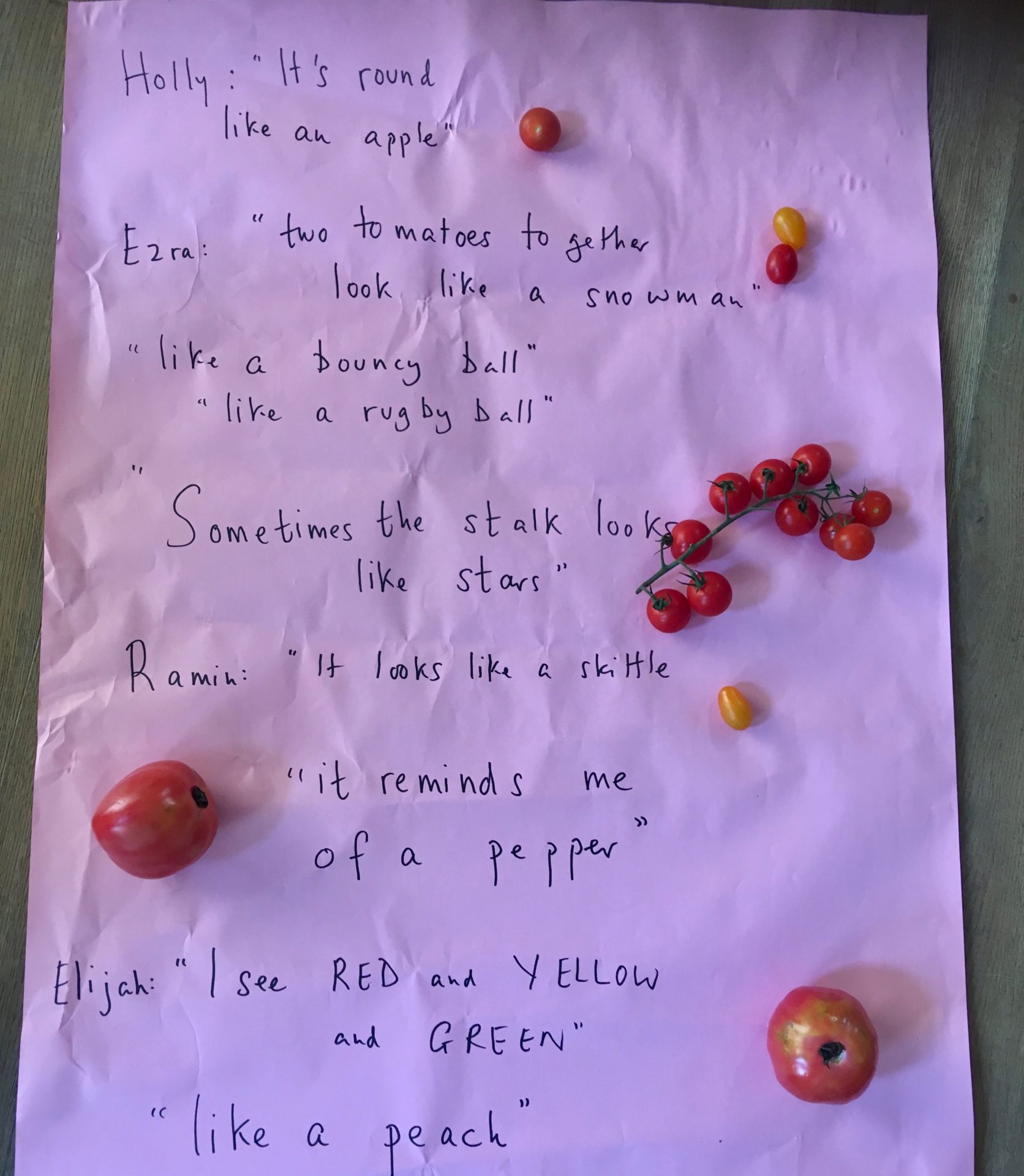

The key to TastEd is the use of all our senses, not just taste. By allowing children to explore food, without pressure to taste or judging them for their preferences, they can develop a completely new relationship with foods they might otherwise reject. Think about how loud celery is – and how silent strawberries are. Children listen to food with earplugs or ear-defenders on. Or what about how a food feels, looks, or smells? The children build word banks and develop ever-more imaginative ways of describing what they see, hear or smell, before they might taste the food. “This approach works with the natural curiosity of children. If they’ve looked at the food with their other senses, then they usually want to taste it”, explains Jason. “If you sniff a tomato, you are that much closer to trying it one day”, adds Bee.

When – and only if they want to – they do put the food into their mouth, they are encouraged to continue thinking descriptively and comparatively, rather than simply react by expressing like or dislike. Asking children whether the olive is sweeter than the anchovy, produces very different results – and from children who would likely never have tried either.

The approach to TastEd is simple. There’s a handbook and some lesson ideas and resources for schools – which can also be used for anyone wanting to experiment at home. The ambition, however, is huge: influence policy to make food education a priority across schools, and have TastEd taken up nationally by the UK’s Department for Education with the aim of improving health through education. Currently, healthy eating is not part of what is measured at schools. As Jason points out: “You won’t lengthen your life by learning good grammar – but you could by developing a confident relationship with food.”

“We know that for the lowest income families, 42% of income goes on food: so encouraging kids to try, and want, a wider range of foods can present new challenges for families”, he continues. Schools need to play a role in closing the health gap, and providing the fruit and vegetables that children need. Washingborough uses part of their pupil premium funding to give children fresh fruit and veg every day.

There are ideas for the application of TastEd’s approach in a much wider variety of settings such as food banks or eating disorder clinics. In Finland, Sapere is now being used to expand the food choices of the over-70s. The first priority, however, is to establish the idea across the primary school sector and build the evidence base for its impact. TastEd’s third founder, Abby Scott, is a former teacher who is helping develop a set of core lessons that support the existing British curriculum. The Soil Association is working to promote TastEd in a number of schools in Warwickshire with high levels of deprivation.

The hope is clear. Bee sums it up: “We want children to carry with them this completely different relationship with flavour and with food into the wider world. We hope they will be drawn towards healthy food with joy.”

AtlasAction: Whatever your age, try to eat with all your senses and learn new tastes: feel the fuzz on a peach, listen to the snap of the celery, tear a mint leaf and inhale deeply. Also sign up at the website to become part of TastEd’s growing network.

? ►AtlasEvent: Meet the UK’s most influential food writer at Fixing the Future Festival! Bee Wilson is the chair of TastEd, as well as the author of six best-selling books – including ‘The Way We Eat Now’ – and regular writer for The Wall Street Journal and The Guardian. This ticket price is so good it’s edible.

Project leader

Bee Wilson, author, and Jason O’Rourke, Headteacher at Washingborough Academy

Support the Atlas

We want the Atlas of the Future media platform and our event to be available to everybody, everywhere for free – always. Fancy helping us spread stories of hope and optimism to create a better tomorrow? For those able, we'd be grateful for any donation.

- Please support the Atlas here

- Thank you!