Colombia (Medellín)

A powerful mini-computer ‘teaching assistant’ is revolutionising Latin American education and can help bridge the pedagogical divide between the world’s richest and poorest schools. The device pools and distributes global teaching resources and could be a game-changer for the global south.

“We need to give teachers the resources to create the kind of classes that 21st century students need.”– Juan Manuel Lopera

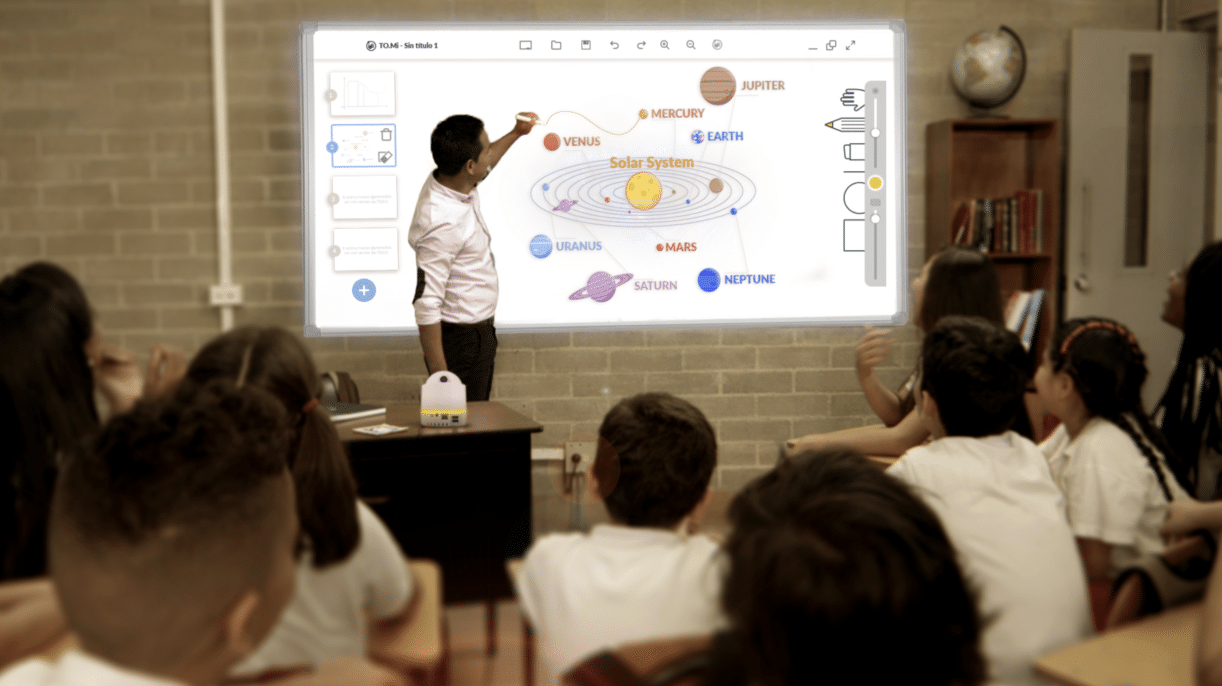

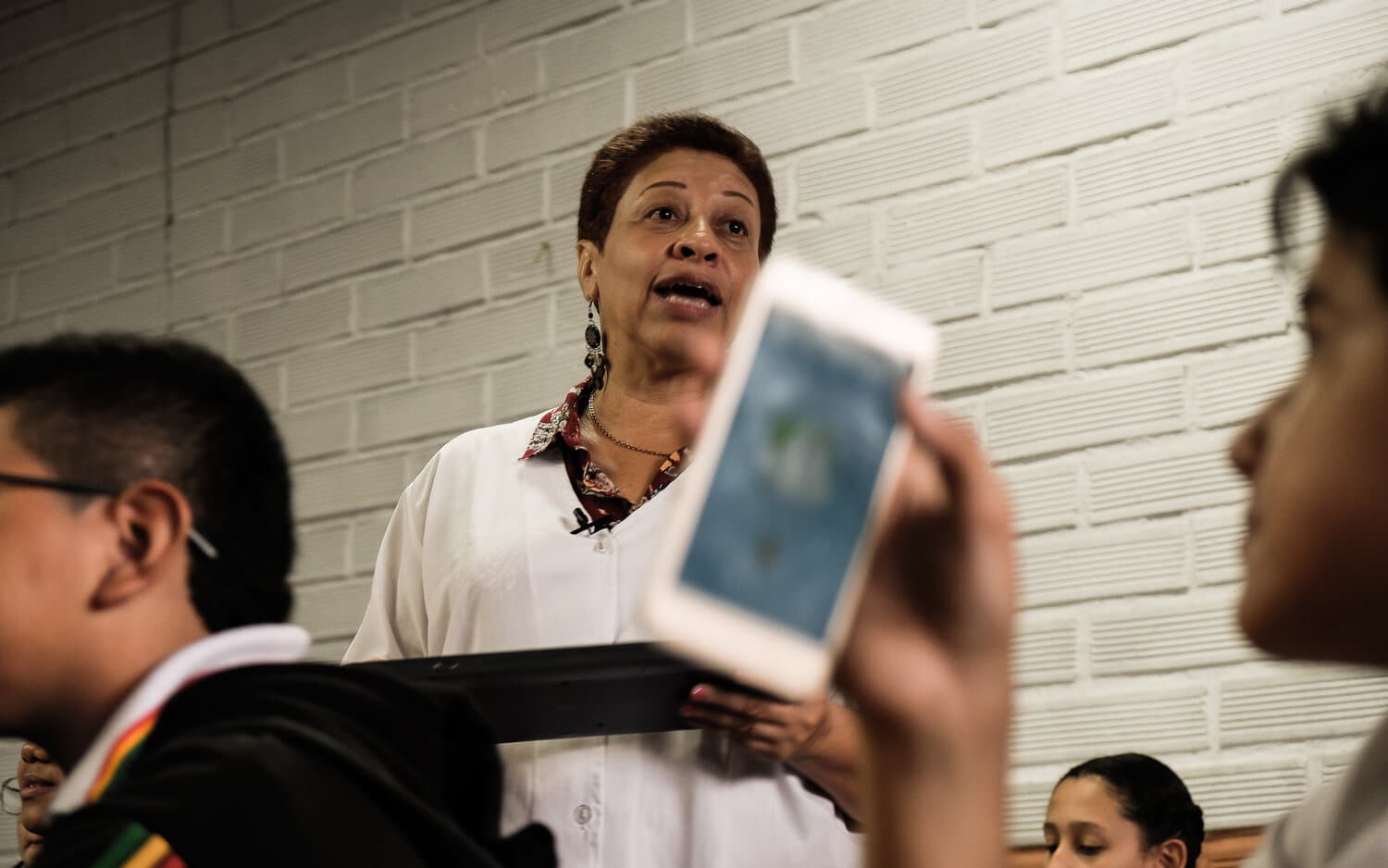

Picture this: around 20 teenage students fidget away in one of the better schools in the emerging Colombian metropolis of Medellin. A mildly-chaotic din fills the room as the kids, each brandishing a smartphone or tablet, clamour and appeal in the direction of their teacher, who’s seemingly orchestrating the mayhem by use of a wireless keyboard.

As images and questions about the medio ambiente (environment) flash up on a TV at the front of the class, it becomes apparent the kids are using their gadgets to play a series of interactive games and quizzes. It feels more like an arcade than a classroom.

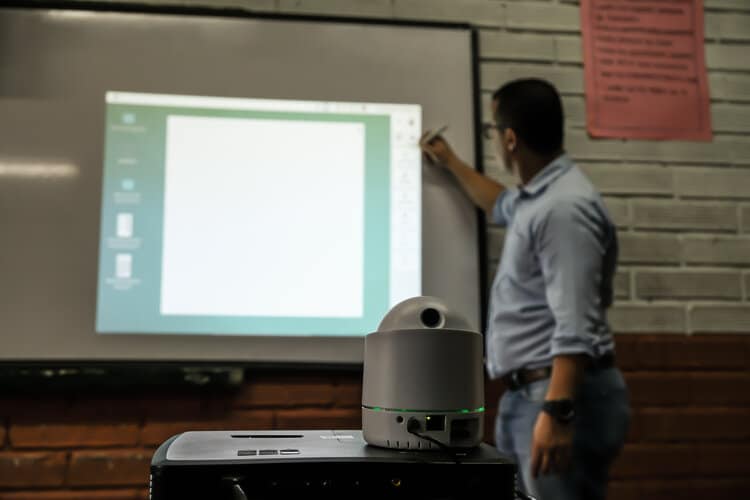

The machiavellian genius behind this baffling parallel universe sits inconspicuously on the teacher’s desk at the front of the class: a cylindrical plastic device simply referred to as TOMi.

At its heart, TOMi is a piece of technology aimed at simplifying the day-to-day tasks of teachers, allowing them more time and resources to create inspiring lessons: from planning classes with the use of thousands of interactive resources to awarding skills badges; creating tests and marking them automatically; building data-driven school reports; using augmented reality to bring subject material to life; connecting gadgets to play interactive games and quizzes; communicating with parents, and other such pedagogical delights.

The device can be connected to a TV or smartboard, or just project onto a blank surface; and can be controlled via an optical pen, keyboard, mouse or even a smartphone. The students connect to the device by scanning a barcode with the cameras on their smartphones; alternatively, TOMi can scan and mark the written answers on their papers. At the end of the exercise, the device sends a spreadsheet with all the students’ marks.

Behind TOMi is a Medellin-based education technology company called Aulas AMiGAS. As well as the technology, it provides training for the teachers in typically more deprived regions.

The device itself costs around $500, and to access the content on the platform there are three tiers of subscription: free, pro ($7 month) and annual pro ($6.5 month for one year + TOMi Play). The company mainly markets its wares at local authorities of cities and municipalities. But if a teacher wants to buy TOMi they have the option of combining the device and content into a monthly subscription.

“Innovation in education is completely dependent on the teachers,” states Aulas’s founder, Juan Manuel Lopera. “They make the real difference in the classroom and if they can’t understand what the students need, no amount of technology is going to make a difference. So we need to improve the capabilities and skills of those teachers.”

Juan uses the analogy of Iron Man: an average bloke who, equipped with the right hardware and data, is transformed into a superhero. “In emerging countries, teachers are usually just very normal people who are trying their best,” he explains. “In Singapore, you’ll find high-school teachers with PhDs, but in Latin America they’ve typically only completed secondary education. We recently visited Valle del Cauca (a region on Colombia’s Pacific coast) and some of the teachers didn’t even know how to write. So we need to provide the right tools to turn those kinds of teachers into superheroes.”

TOMi has been designed to mimic what Apple did with the iPhone, which integrated a mobile phone, mp3 player, GPS, computer, etc, all into one device so they became easy to master for even the most neanderthal technophobes. TOMi does the same for education technology: integrating all the tools teachers need to prepare classes, teach in the classroom, grade exams, learn new teaching techniques, and communicate with parents. And the technology doesn’t require any existing infrastructure in order to work. “Some of the schools that use TOMi don’t even have walls,” comments Juan. “They’re poor schools in the middle of the jungle. They just hang up a sheet and have TOMi project onto it.”

Juan is driven by his own experience: he grew up in one of the poorest neighbourhoods in Medellin during the brutal violence of the 1990s and puts his own social mobility almost entirely down to one teacher. “He figured out the “gap” I had and how to close it,” he says. “The teacher is the key, so we need to figure out how to close the gap between good and bad teachers if we want to close the gap between poorer and richer students.”

The UN’s education agency, UNESCO, estimates that in developing countries 200 million people aged 14-25 have not even completed primary school. Technology can help bridge the divide, but often the barrier to its widespread application isn’t the money but the capacity of the teachers to use it. In the 1990s, Medellin was officially the world’s most murderous city.

When Juan was 12, a man called Sigifredo Cortez began teaching his class physics, maths and religious studies. He encouraged each pupil to self-learn in an area that interested them, which for Juan was programming. The results were transformational and many of Juan’s classmates would go on to have similarly successful careers. At the age of 17, he graduated and set up a company, which designed software that allowed for remote assistance of computers. By the time he’d turned 19, he’d sold that business for $500,000. And with the proceeds, he moved his family out of town.

“That’s when I realised just how drastically my teacher had changed my life,” he remembers. “And that inspired me to set up Aulas AMiGAS with my former classmate, Alejandro Sepulveda, in order to create more teachers like Cortez. Aulas AMiGAS opened its doors in 2009.

Today, there are over 100,000 Latin American teachers using Aulas’s technology, spanning Colombia, Mexico, Ecuador, Guatemala, Bolivia, Argentina and Costa Rica. Every month, over a 1,000 new classes are created on the Aulas platform. The company employs over 200 people, with offices in five Colombian cities and direct operations in Mexico, Ecuador and Argentina.

Aulas had revenues of approximately $10 million in 2019, when TOMi was incorporated as a separate company to Aulas — making $1.3 million. The success of the business saw him named among MIT Technology Review’s Innovators Under 35 in 2016.

“Bridging the education gap between poorer and richer nations isn’t a job for just one company, or one virtual community, but the role such a company can play in society is huge.”

In the long run, it all forms part of Juan’s dream to create a global “army of teachers” just like his own Sigifredo Cortez. “Just imagine what he could’ve done with one of those,” he says, nodding toward the little plastic device sat on the shelf.

Read more ► This was adapted from a 10 minute read in Struggles from Below.

Bio

Struggles From Below is an online magazine dedicated to shining a light on individuals engaged in changing the world from the bottom up; telling the stories of those trying to improve our system of living to achieve a more humane and ecologically-harmonious existence.

Project leader

Juan Manuel Lopera, CEO, TOMi Digital

Support the Atlas

We want the Atlas of the Future media platform and our event to be available to everybody, everywhere for free – always. Fancy helping us spread stories of hope and optimism to create a better tomorrow? For those able, we'd be grateful for any donation.

- Please support the Atlas here

- Thank you!

INEM José Félix de Restrepo is a school in the Poblado district of Medellin

Juan Manuel Lopera, the founder of Aulas AMiGAS and TOMi, was inspired to create the business by the influential role a high-school teacher played in his own social mobility

The process involves a diagnostic evaluation of the teachers, who are classified technically and psychologically, and provided with a personalised training programme

In the 1990s, Medellin was officially the world’s most murderous city

7,000 Latin American teachers pay for TOMi out of their own pocket