Indonesia (Bandung)

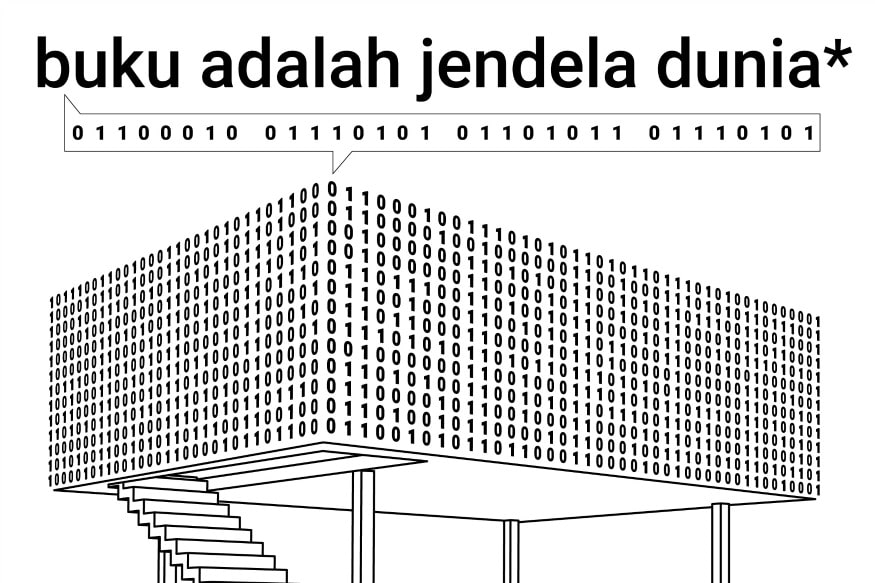

Is there anything sweeter than a library made from ice cream buckets? Yes. One whose facade spells out “books are the windows to the world” in binary code.

Add a community space that has been created to help raise awareness of plastic waste and it’s a sweet recipe for a better future. The books are the cherries on top.

In 2018 Dutch architecture firm SHAU created a ‘Microlibrary’ above a stage in a small square in the heart of the city of Bandung in Indonesia – to encourage people to hang out and develop a love for reading. As well as being a resource of books, the floating box shelters and shades the community area from the country’s tropical climate. And the whole thing is made from upcycled plastic containers.

Having always focused on creating socially and environmentally sustainable and innovative projects, this first, and now award-winning, Microlibrary was SHAU’s first foray into the world of education. Their aim is to combat Indonesia’s high illiteracy and school dropout rates by creating a series of low-cost cultural facilities around the country.

SHAU are Indonesia-born Daliana Suryawinata and German Florian Heinzelmann. The married couple met while studying at the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam, Netherlands. There they learned that spaces have a tremendous impact on society. Interested in the problems that Indonesia faces – such as infrastructure, flooding, environment and rapid urbanisation – they moved to the Southeast Asian nation in 2015.

Kids are not big readers in Indonesia. “Books aren’t so much in the public mind. We want to change that by bringing low-tech Microlibraries and books into Kampung and village-like locations,” Florian tells us. “We are plugging the Microlibrary into existing urban and communal fabric, not placing something into a vacuum hoping that the library gets accepted and used, but adding the library to places in the city which are already frequented.”

The science-fiction loving Florian believes that the role of culture and creativity is to create awareness of a problem in the first place. “That may be the role of journalism, art and the avant-garde. Creating tangible solutions is the role of governments, architecture, design and the mainstream.”

When SHAU explored the immediate surrounding of the Bima Microlibrary, they saw small vendors selling used plastic ‘jerrycans’ and thought they could use those for its facade. They shade the interior, let daylight pass and enable enough cross ventilation – but they were not available in the quantities they needed. Florian’s architecture often focuses on daylight. “After a bit of research, we finally found a online vendor selling used ice cream buckets as an alternative to Tupperware-like products.”

As well as causing issues with public health and flooding, the plastic waste problem in Indonesia is especially severe as the country is dependent on income from tourism, yet soils its own beaches. The ‘fun fact’ that the library’s exterior is made from 2,000 ice-cream buckets offers an entry point for discussing plastic garbage problems.

What’s more, the facade’s pattern of open and closed translucent tubs is not random. They have been arranged in binary code – as zeroes and ones – to encode a ‘secret’ message. Bandung’s forward-thinking Mayor Ridwan Kamil, who is one of the patrons of the project, supplied the meaningful inscription ‘buku adalah jendela dunia’ (Indonesian for ‘books are the windows to the world’).

Thinking outside the (ice cream) box

On a cultural level this indirectly connects analogue and digital media, and the act of deciphering symbols into words and sentences. “For somebody who cannot read, the content of a book is not understandable. It appears to be a arrangement of symbols, which may have some form of logic, but the meaning is entirely elusive. Maybe we evoke something similar when one looks at the Microlibrary Bima.”

It is built in accordance to the Deputy Mayor of Cirebon’s program, ‘Pojok Baca’ or Reading Corner.. SHAU is aware that in Indonesia their projects require a “top down and bottom up approach”. As much as you need the support of a local leader to make sure that a project is running well from a legal and administrative standpoint, it’s vital to talk and listen to the local people.

They have since created more Microlibraries and structures around Indonesia, from the city of Cirebon tof Bojonegoro, East Java.

When designing a Film Park in Bandung with terraced seating for watching movies, the couple discovered that the most important part of the park was the artificial lawn in front of the screen, especially when nothing is being shown. “People start behaving as if they are at home. They don’t litter, they take of their shoes, kids play and roll around. You start to understand that you not only created a film park, but positive behaviour – an urban, communal living room.”

While SHAU’s mission is to rekindle interest in culture, the team has witnessed how urban spaces have the power to enhance or deny interaction among people. And there’s nothing vanilla about that.

AtlasAction: SHAU would like to create an organisation to support development and outreach for Microlibraries. Get in touch here.

Project leader

German Florian Heinzelmann and Daliana Suryawinata, Co-founders

Partners

This project has been selected as part of CultureFutures, a new storytelling project that maps creative and cultural projects with a social mission – and the artists, collectives and entrepreneurs behind them.

Atlas of the Future is excited to join forces with Goldsmiths Institute of Creative and Cultural Entrepreneurship and the British Council Creative Economy.

Support the Atlas

We want the Atlas of the Future media platform and our event to be available to everybody, everywhere for free – always. Fancy helping us spread stories of hope and optimism to create a better tomorrow? For those able, we'd be grateful for any donation.

- Please support the Atlas here

- Thank you!

Photos: SHAU/Sanrok Studio