Kenya (Ukunda)

Can words posted to social media suggest where a genocide might happen? This rumour police in Kenya fights misinformation with an SMS service that acts as a fact-checker.

Misinformation has become a major problem as social media enables rumour-spreading at a speed that wasn’t possible in the pre-digital era.

This was one of the factors that led to Tana Delta violence during 2012 and 2013. When Kenya was warming up to the general election, clashes killed nearly 170 people and displaced tens of thousands – leaving increased hatred and mistrust between the Orma and the Pokomo, the two most affected ethnic communities.

There is still no local media in the area, but residents of Tana Delta use technology: 81% own mobile phones and 45% of those phones are internet-enabled. As this is how falsehoods flourish, a free mobile phone-based reporting information system has been set up as a rumour verification hotline, mapping and countering false misinformation on a day-to-day basis.

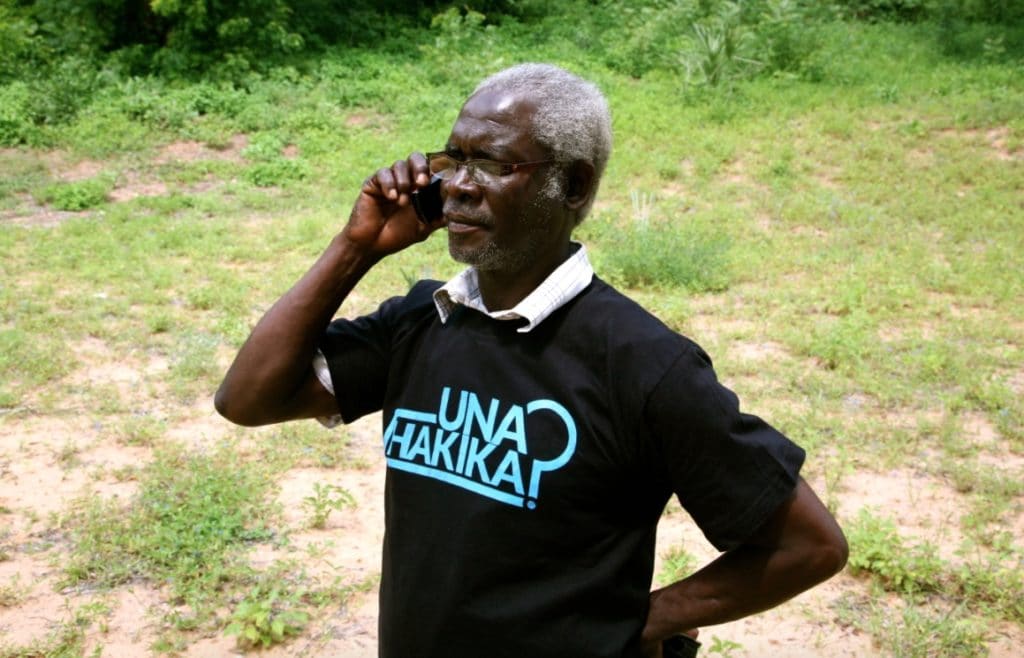

Swahili for “Are you sure?” Una Hakika’s motto is “amani huanza na ukweli”, which means “peace begins with the truth”. That’s right, these rumour police in Kenya are tackling bloody conflict via SMS.

Users report rumours to through SMS, phone calls, website or to a trained community ambassador. They are verified via local authorities, NGOs, social media and mainstream media. Then the team reports back to the community whether the rumour is true or not. One of the goals of Una Hakika is to fill the information gap, with preventing incendiary rumours leading to tensions and loss of trust through interactions among communities in order to reduce chances of violence recurring.

One of the rumours reported as false this year was the following: “A baby sent from Heaven was born at midnight and told people to make black tea without adding sugar or anything else and take it as a coronavirus vaccine. The baby then died at 3:00 AM.”

The rumour was reported via SMS by an anonymous person and the platform confirmed: “This information has no logical basis and was spread maliciously with the intention of discouraging people from taking medically approved tests for COVID-19.”

The brainchild of Canada’s The Sentinel Project, the team even purpose-built WikiRumours software for moderating misinformation and disinformation: “Our goal is to use a combination of technology, the information service and training to create a lasting solution to the problem of rumours and misinformation”, Executive Director Christopher Tuckwood (pictured below right) tells us. “This means encouraging people to be more sceptical and questioning of the information they hear by word of mouth.”

First met with scepticism, by September 2015 Una Hakika was ranked as the third most trusted source of information behind radio and television in the Tana Delta, sometimes warning of potential violence before the police knew about it. Government officials can now synchronise efforts with the system, ensuring that they don’t waste time or resources reacting to falsehoods.

Una Hakika is expanding into other parts of Kenya, like the Kakuma Refugee Camp, and the plan is to grow into other countries such as Myanmar and other violence-prone areas around the world. The project also has a branch in Uganda and South Sudan called Hagiga Wahid.

AtlasAction: You can report a rumour here.

Project leader

Christopher Tuckwood, Executive Director, The Sentinel Project

Support the Atlas

We want the Atlas of the Future media platform and our event to be available to everybody, everywhere for free – always. Fancy helping us spread stories of hope and optimism to create a better tomorrow? For those able, we'd be grateful for any donation.

- Please support the Atlas here

- Thank you!

The Orma community of Kipao are traditional pastoralists, raising cattle, sheep and goats along the Tana River

Curious community members congregate in the shade to learn about the Una Hakika project

Chris gives a summary of Una Hakika to the community while John translates into Swahili

The survey attracts considerable interest amongst the community

Although infrastructure is limited in the Tana Delta, cell towers do provide widespread coverage and mobile phone ownership rates in the area are high