Kenya (Wasini Island)

A coral reef restoration project run by a community of women on a tiny island off Kenya’s south-east coast is reaping dividends for local people.

“Lobsters and octopuses are back!”

Three years ago, coral reef along the Kenyan coastline was almost totally destroyed in some areas. Rising surface sea temperatures had triggered devastating bleaching episodes for the fourth time in less than two decades, and with the whitening of coral came a dwindling of marine life. Overfishing only exacerbated the problem.

For coastal communities dependent on the sea for their livelihoods, the degradation of the coral reef and its effect on the marine ecosystem threatened to overturn an entire way of life. In some areas surveyed by the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), as much as 60-90% of coral was destroyed.

A fightback was needed and so the institute began working with local communities to rehabilitate degraded coral reefs along the country’s coastline. Among the areas targeted was Wasini Island, a tiny strip of land off Kenya’s south-east coast. The results have been startling.

Women on the island have led an initiative to restore degraded coral that has shown how coral restoration techniques can revive marine ecosystems and create sustainable livelihoods for communities that depend on fishing and eco-tourism.

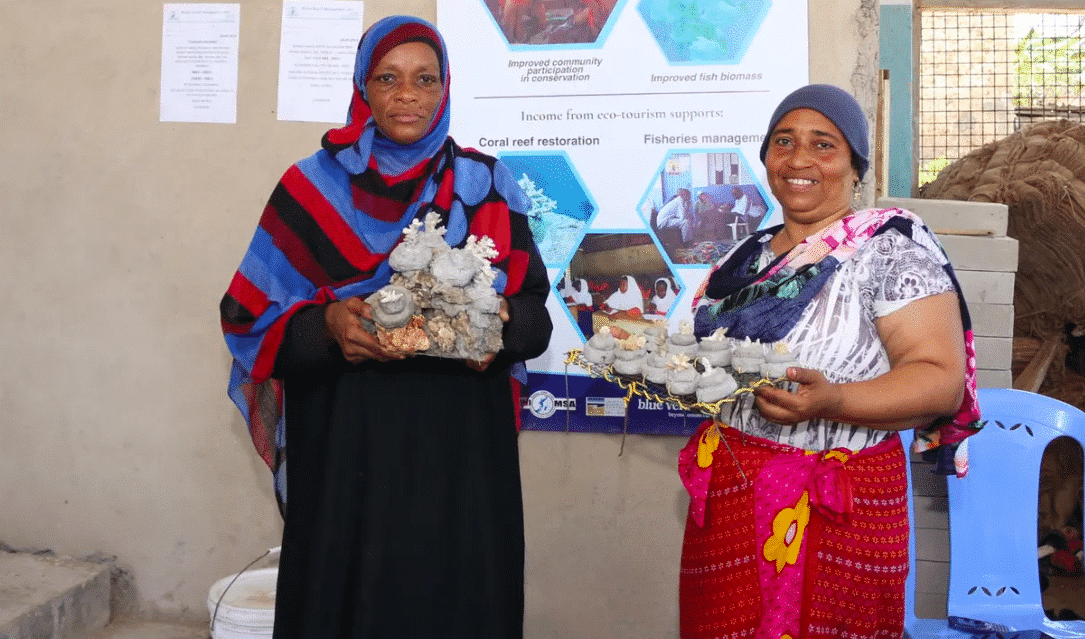

“The fish have started coming back since the restoration activities began,” says Wasini Beach Management Unit‘s Nasura Ali (pictured below with Nazo Yaro and the reef they have constructed). The WBMU has about 250 members, of whom roughly 150 are women. More than 40 people have been trained in restoration techniques.

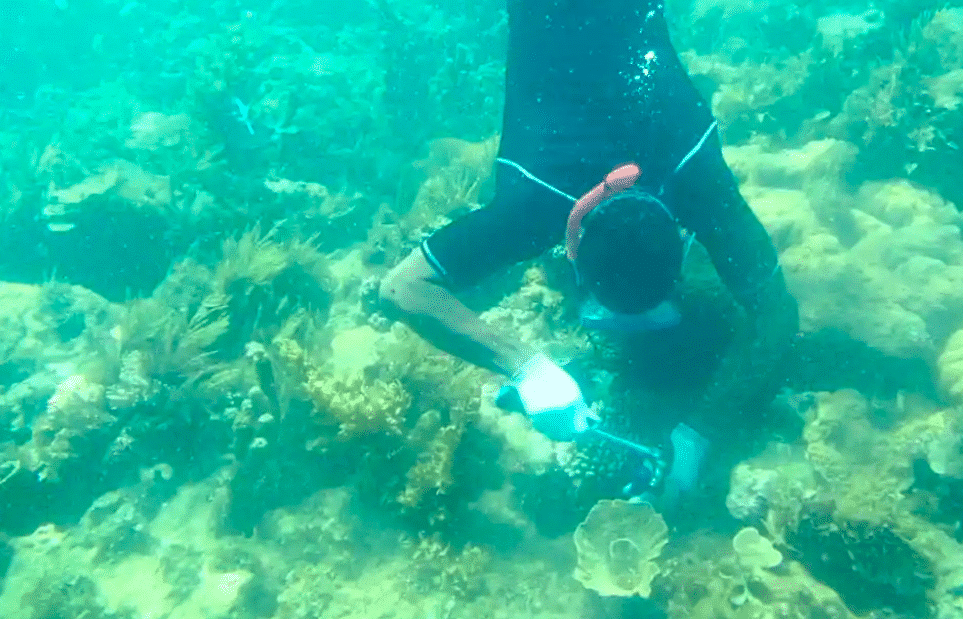

A year-long study by the KMFRI had tested the viability of raising coral fragments from areas affected by bleaching events, explains Jelvas Mwaura at the KMFRI’s department of marine environment and ecology. Many of the corals transplanted from coral gardens to degraded reef areas for the study survived, providing new habitats for fish species including jacks, groupers, emperors and sweetlips.

This success led to funding from the Kenya Coastal Development project (KCDP). Locals on Wasini Island have since grown more than 3,000 corals.

Coral reefs provide shelter and breeding grounds for hundreds of species of marine life. Fish populations in waters around the island have increased three times as much as in other areas, says the KMFRI.

“Not only have these conservation efforts increased fish numbers in protected areas but the rising populations are spilling over into non-protected areas, benefiting many more people,” says Dishon Murage, a consultant with US-based environmental conservation organisation Seacology and lecturer at the Technical University of Mombasa.

The women of Wasini Island have also been restoring fish populations by cultivating seagrass. Overfishing of certain species, such as trigger fish, had led to the disappearance of seagrass because trigger fish fed on the sea urchins that devoured it. Using gunny bags made of sisal to protect the seedlings and prevent them from getting washed away, the women replanted seagrass seedlings on the ocean floor.

In addition to providing food, seagrass plays a key role in the overall coral reef ecosystem, providing shelter to juvenile fish after they hatch by shielding them from strong waves until they mature and move into the coral reefs.

Dishon, who has been working with the people of Wasini Island for more than a decade, says the coral restoration has also boosted ecotourism. Before the conservation project, only 30% of the community relied on ecotourism for an income. “This rate has gone up to nearly 80% today,” says Dishon. Tourists pay a nominal fee of 500 Kenyan shillings (£3.80) to experience the marine environment, while locals are charged about 102 shillings.

Nazo Yaro, who is also part of the marine conservation effort, says educating fishermen to stop indiscriminate fishing, especially in vulnerable areas of the reef, has also helped. “Lobsters and octopuses are back as a result,” she says triumphantly.

Both Nasura and Nazo have been trained in making artificial reefs courtesy of a joint initiative by the KMFRI and the UN development programme through the Global Environment Facility Fund, which supports community-led environmental conservation efforts.

Coral reefs can be created in various ways. One method, widely practised in Japan and Malaysia, involves the use of concrete blocks. “However, it is very expensive, because it demands a lot of cement and sand,” says Jelvas.

Since the project aims to increase coral restoration in a vast area of roughly 2 hectares (4.9 acres), locally available materials are used instead of concrete. Rock boulders found on the shoreline, and held together with hydraulic cement, are used to create artificial reef structures.

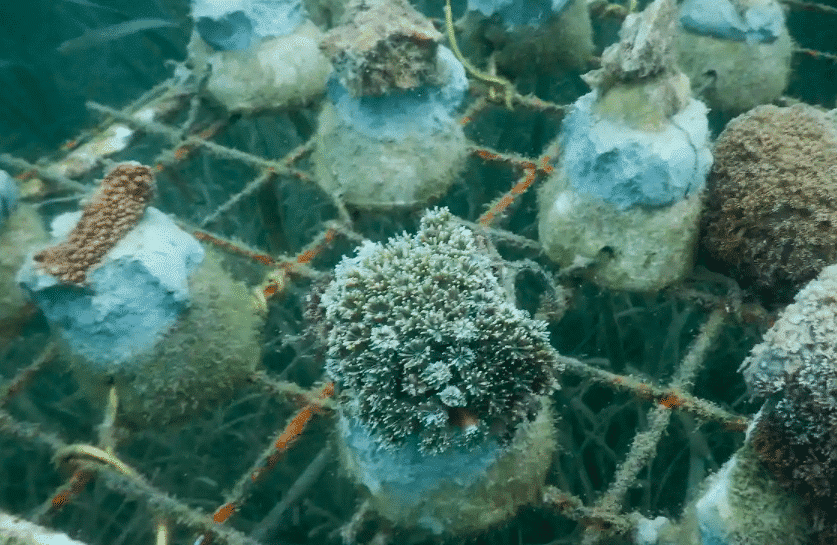

But before corals are planted on these man-made reefs, they are raised in a nursery, a process that takes three to four weeks. “The nursery ought to be a suitable area free of sedimentation, strong currents and boat traffic, where the water is mostly free-flowing,” says Mwaura.

Visual observation indicates that corals transplanted in this way have a survival rate of 75%. Research carried out by KMFRI in 2013 found that 15 out of 32 coral species studied were able to survive. The method was then used for restoration in areas of the ocean chosen by local people.

Kenya and the Seychelles are the only African countries to implement this type of coral reef restoration, with Kenya lighting the way for such efforts along the Indian Ocean coast as long ago as 1968, when Malindi national marine park was established.

However, the Seychelles, Madagascar and Mauritius are among countries that have overtaken Kenya in coral reef conservation by securing financial support, as well as effective monitoring and law enforcement.

AtlasAction: The project is funded by NEMA’s Adaptation Fund and Implemented by Coast Development Authority. Learn more about their coastal projects here.

Project leader

Nasura Ali & Nazo Yaro, Wasini Beach Management Unit

Support the Atlas

We want the Atlas of the Future media platform and our event to be available to everybody, everywhere for free – always. Fancy helping us spread stories of hope and optimism to create a better tomorrow? For those able, we'd be grateful for any donation.

- Please support the Atlas here

- Thank you!

Hello, I am writing an article for Counting Coral, a coral reef initiative building nurseries for corals in Fiji. Might I reach out to you for a few quotes on your progress? Thank you for your time.