United Kingdom (London)

It started in a shed. Indeed, the shed is still there, in Peter Dearman’s backyard, which you can find in the old English market town of Bishop’s Stortford, Hertfordshire. Through its windows you will often see Mr. Dearman, probably with a spanner in his hand. He’s the archetypal shed-hobbyist: jeans, anorak and totally obsessed with mechanical apparatus. His neighbours jokingly used to call him ‘the neighbour from hell’ thanks to the discarded bits of machinery that lay about his property. Today they’re slightly more respectful.

As they should be – because, early in 2000, Peter solved a problem whose solution had evaded the engineering world for a century. In doing so, he unleashed a coming revolution that has the potential to save millions of lives. And he did it with a can of antifreeze.

It’s not an idea that immediately makes sense to most of us. When we think of energy we tend to think of hot things: fire, steam, warm computer batteries… Cold is something we associate with a lack of energy. But our intuition is misleading. Two objects of different temperatures brought into contact will exchange energy (as they try to get to the same temperature) even if those temperatures are both below freezing point – and if you piggy-back on that exchange you can do useful work.

Peter, of course, wasn’t the first person to realise this, but he did become the first person, many years later, to use the concept to create a machine that could help to save millions of lives by changing the way our food system works – ‘The Dearman Engine’.

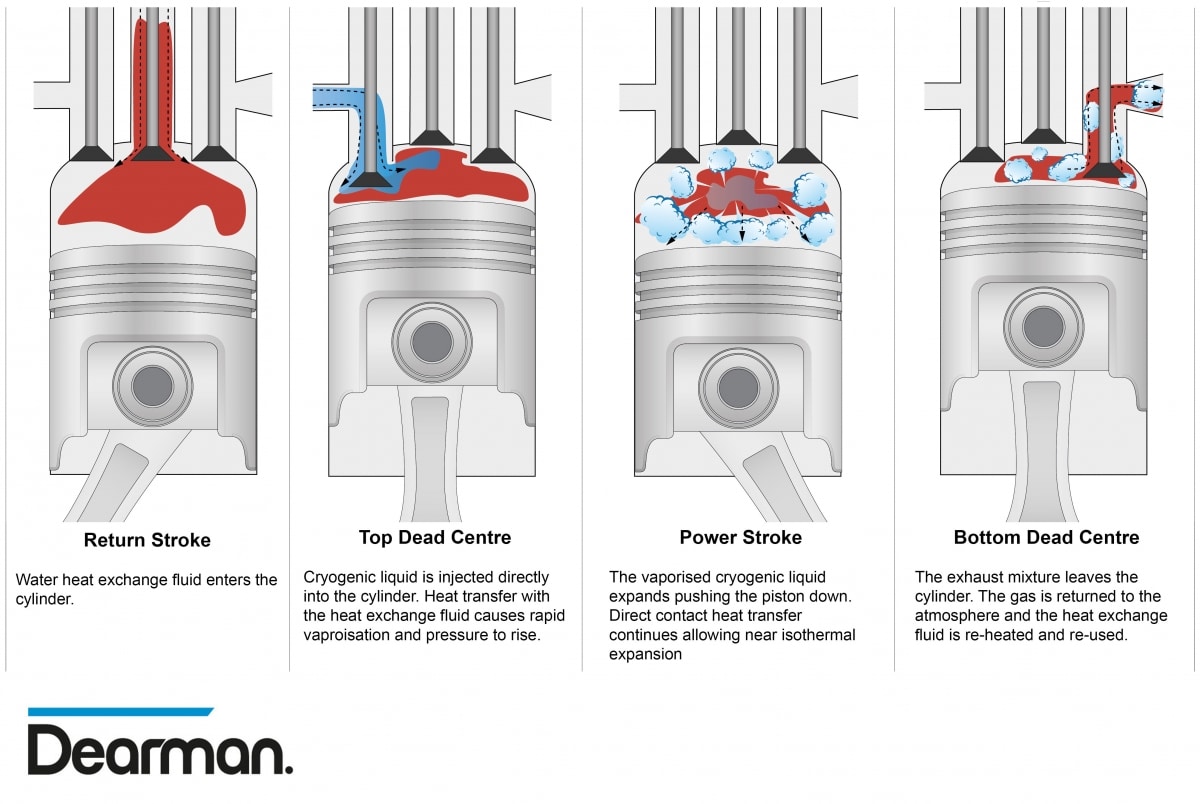

Dearman Engines work on exactly the same principles as a steam engine, except they’re powered not by steam (water gas) but by another gas, which, when you first hear about it, seems to make no sense at all. The gas that drives a Dearman Engine is literally thin air.

It’s hard to think of air as a liquid, but like most substances, air can exist as a gas, a liquid or a solid, if you compress and cool it enough. What’s more, it will return to its gaseous state almost instantly if you open a valve on a tank of the stuff.

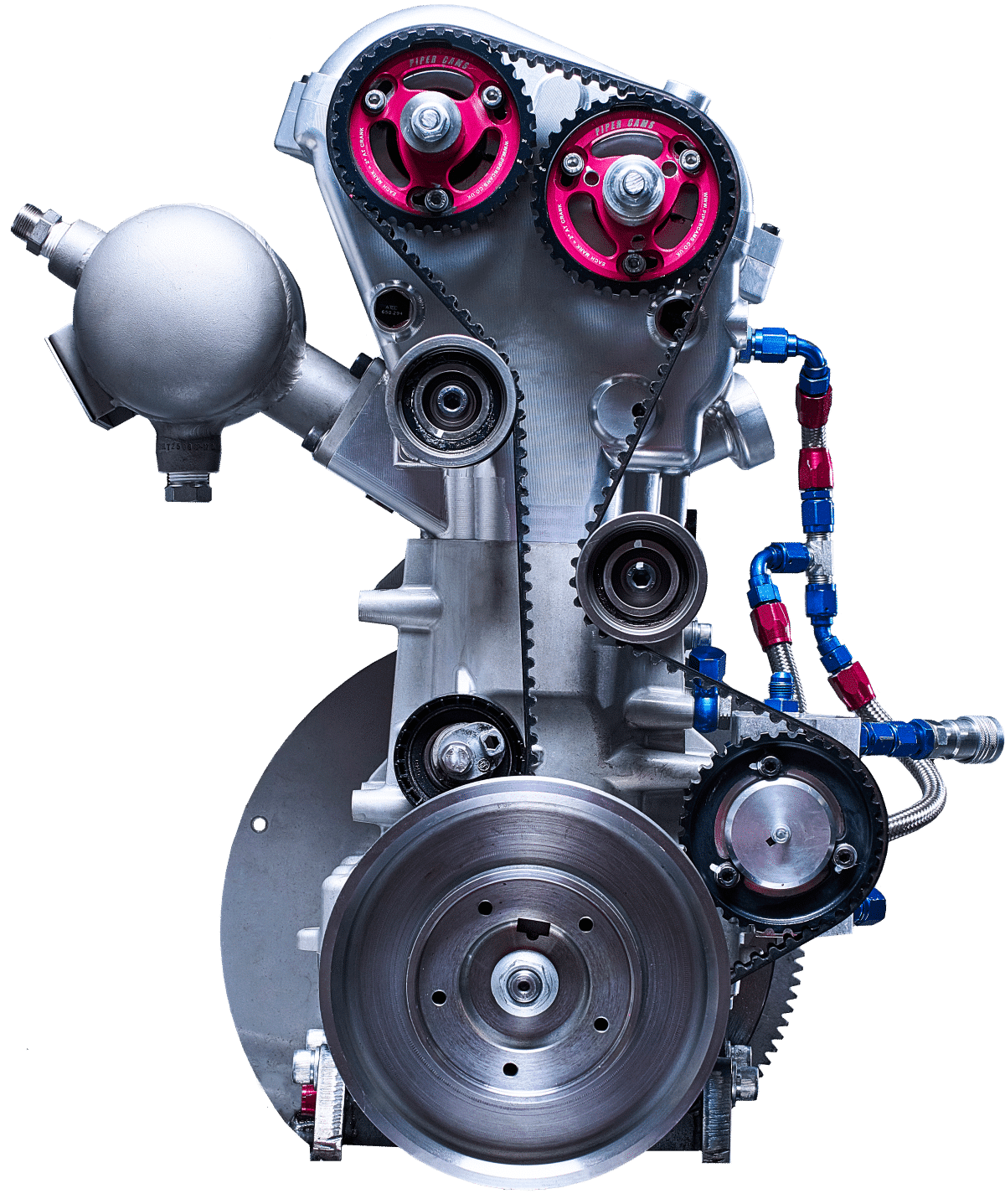

Peter realised an air engine would never fully compete with its fossil fuel counterpart on power, but he knew he could raise its power to useful levels – creating a cheap-to-run and completely clean engine that could do useful work. “What was needed was isothermal expansion.” (This mean keeping the air in the piston at the same temperature even as it expands.) ‘Iso’ comes from the Greek isos, meaning ‘equal’ or ‘uniform’.

Peter wandered into his shed and hacked his lawnmower to run on liquid air, but with one crucial innovation. He injected antifreeze (a liquid specifcally designed to be a particularly efficient heat exchanger) into the piston chamber on each stroke. Now heat from outside the piston chamber, carried in the antifreeze, had a far quicker route into it, delivering the isothermal expansion Peter needed. The effciency of the engine leapt. Although he didn’t know it at the time, Peter Dearman, with a keen mind, a lawnmower and a can of antifreeze, had just changed the world.

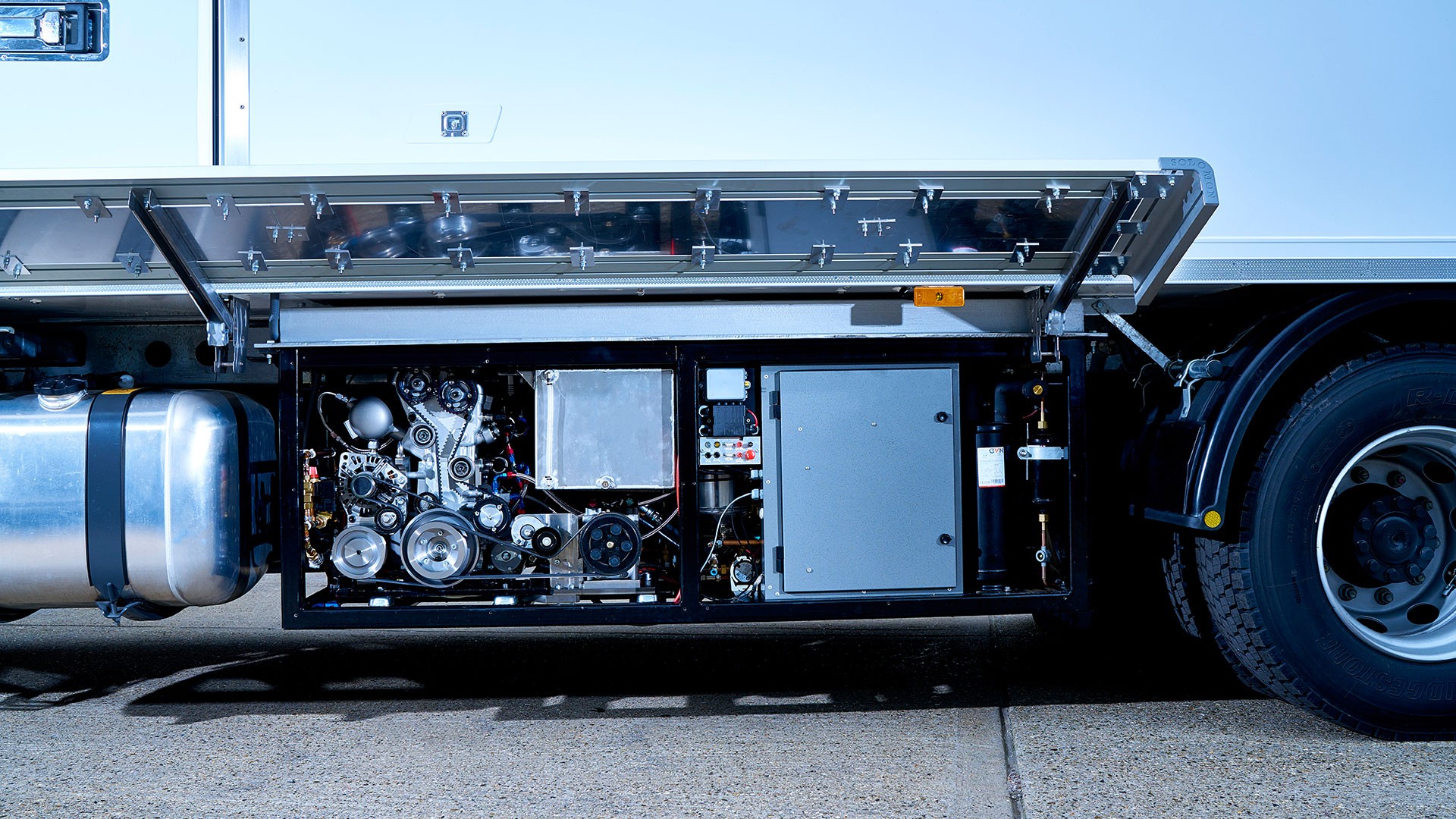

Peter had unwittingly come up with a new technology for refrigeration – and one far greener than the fossil-fuel-powered methods we use today. ‘After we realised we could use it for cooling, things just snowballed.”

What Dearman’s technology could do for the developing world. Imagine farms where liquid air systems provide power and cold at the same time, running, for example, a refrigerated conveyor belt for fruit processing. The ability to minimise waste delivers a massive economic dividend.

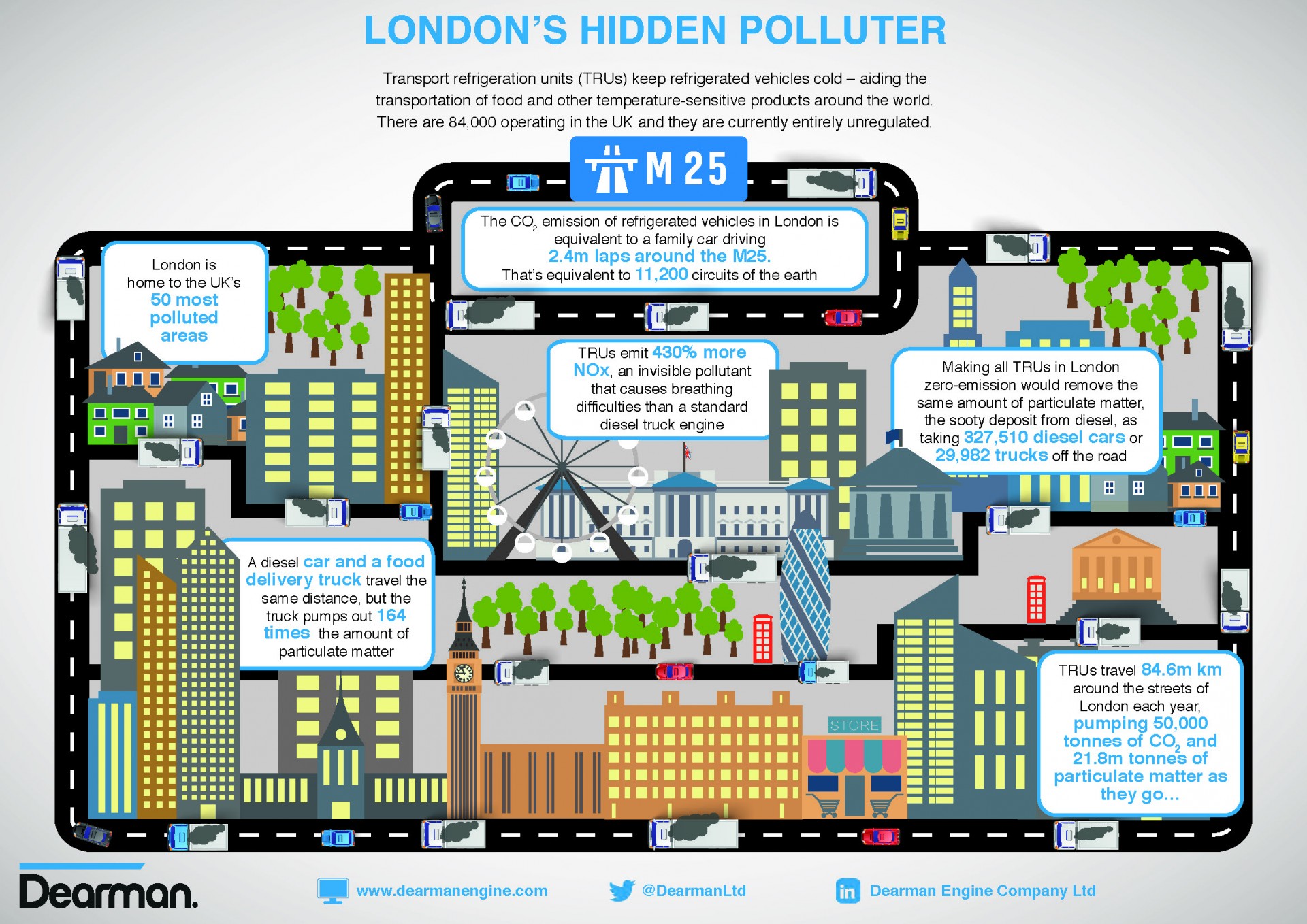

And, while today that cooling and energy could possibly be provided more cheaply using a diesel generator, a new ‘cold economy’ that, at scale, will challenge the cost of fossil-fuel-powered alternatives and come with three key advantages that are hard to compete with. The first is that liquid air is a fuel source that every nation can make for itself. The second benefit is that liquid air refrigeration could significantly reduce air pollution. Dearman engines emit nothing but clean air. But the story doesn’t end there. Because it turns out that Peter Dearman’s antifreeze brainwave has another, potentially world-changing application. The man in the shed might have helped change the world twice.

This is an edited excerpt from Mark Stevenson’s latest book We Do Things Differently: The Outsiders Rebooting Our World.

Bio

Writer, entrepreneur, broadcaster, reluctant futurologist and founder of The League of Pragmatic Optimists. He has written for Radio 4, the Times, Sunday Times, Wall Street Journal, Telegraph, Guardian and New Statesman, and is the author of the critically acclaimed An Optimist’s Tour of the Future. He lives in London and is an adviser to (among others) The Atlas of the Future, The Virgin Earth Challenge, and Civilised Bank.

Project leader

Peter Dearman

Support the Atlas

We want the Atlas of the Future media platform and our event to be available to everybody, everywhere for free – always. Fancy helping us spread stories of hope and optimism to create a better tomorrow? For those able, we'd be grateful for any donation.

- Please support the Atlas here

- Thank you!

Beautiful.

In Africa, we need this dearman engine as an alternative to the fossil over used engines from Japan. Can the dearman engine be fitted on a Japanese 12 tonne reefer truck?

At what cost would i be able to acquire one