United States (New Orleans)

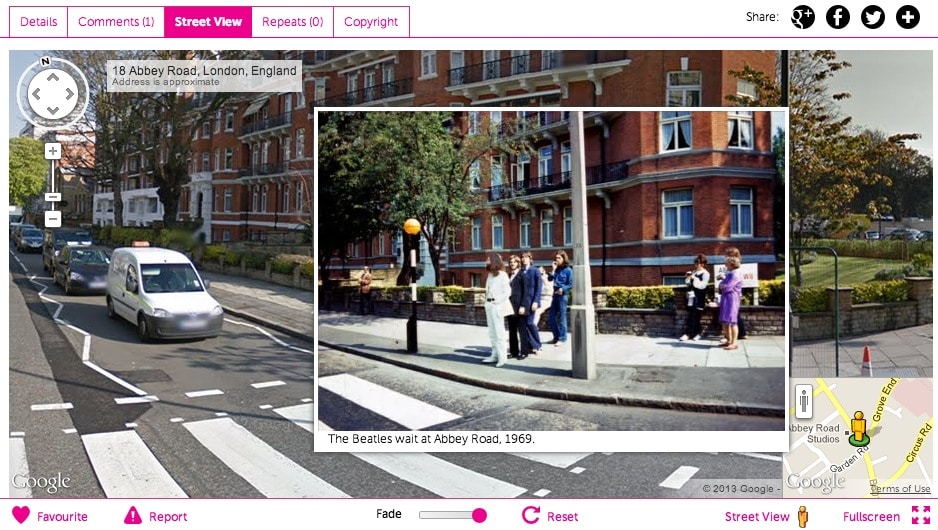

Want to see what London’s Abbey Road looked like in 1969, explore LGBT+ life in the sixties or map the women’s suffrage movement? Prepare to fall down a rabbit hole exploring Historypin – a digital time machine that creates a new way for the world to see and share history – collectively.

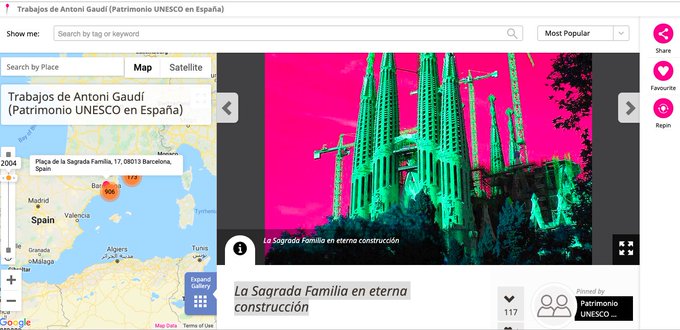

Imagine having access to the most extraordinary stash of old photos, but one you can then add to, so that everyone can compare the world today to how it used to be. Historypin is exactly that: a crowdsourced online, global archive to which people can attach photos, videos, stories, audio files and memories – all pinned to a giant map. And you know how we love a map.

We can thank technology and design for allowing us to open up the fourth dimension and archive history in new, interesting ways; in this instance creating a global archive of pre-internet human memory. The interactive mapping platform brings older and younger people together around an open collection of communal histories – to help spark conversations to close the gap between generations and cultures.

“Historypin helps older people who are working to digitise their memories with the help of the younger generation and helps the younger generation to become more interested in the stories of the older generation” – Hali Dardar

This massive global canvas connects over 4,000 cultural heritage organisations worldwide using Google Street View. The platform allows people to go back to any place at any time in the world, then create location-specific layers of content – merging past and present to see how much a place has dramatically changed, or not.

Historypin’s platform, launched by the award-winning charity Shift London (formerly known as We Are What We Do) was initially set up in 2011 as a way to map the past.”Organisations and individuals could share photos of what their neighbourhoods or towns once looked like; gathering the personal stories of older residents is sometimes the only way to fill in gaps in a town’s historic timeline.

But at its heart was helping people have more conversations and understand each other better. Today’s age is digital, whereas our grandparents lived in an analogue world. A 50 year age gap might make people feel they have nothing in common. However, shared history can allow us to understand each others heritage better to make rich and natural connections – and collective memories.

“The output of cultural heritage work is both innovation and the emotional wellbeing of people – regardless of age – but understanding that older people are part of that,” explains Hali Dardar, Historypin’s Partnerships Manager. “Emotional wellbeing is one of our goals in community-based cultural heritage projects.”

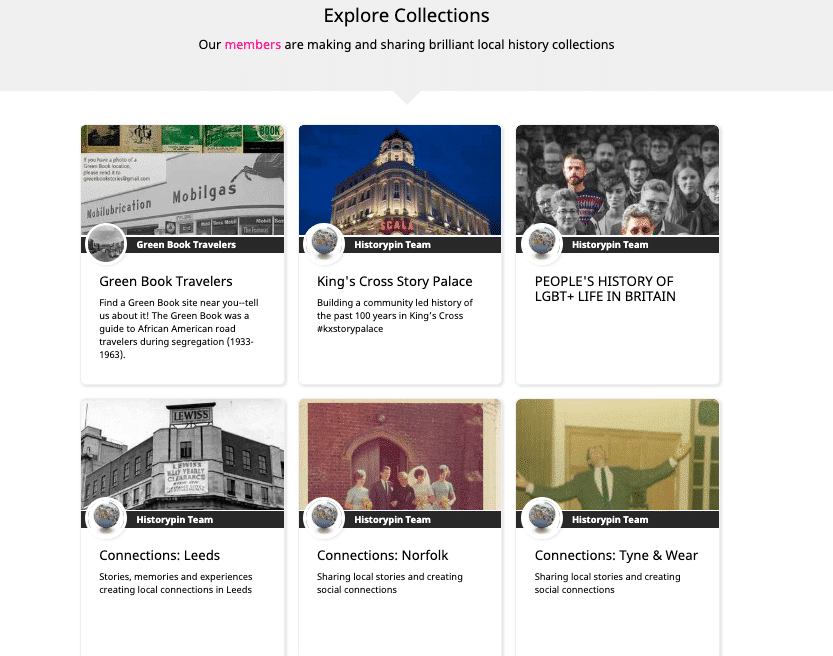

Built by a community of over 80,000 storytellers, archivists and citizen historians, today Historypin hosts 365,951 stories pinned across 2,600 cities (and counting). “Some users post regularly, and it’s clear that it’s become part of their lives, where others may post once only,” Hali adds. “Others use it as a way of digitising their community and others use it as pedagogy, as a way of questioning and pinning things in a specific location.”

As soon as Historypin was released, cultural heritage organisations started using the tool. Small public libraries, museums and community historical societies found it useful to start engaging communities in a way that they had never done before.

With support from the Knight Foundation, in 2017 Historypin developed Storybox – free, hosted two hour workshops in local pubs and libraries all over the world. People pair up, share stories and hear life experiences of people within the various communities. Piloted in 22 public and tribal libraries in New Mexico, Louisiana, New York and Georgia, it propelled a national rollout to public libraries across the US. “What came out of that was intergenerational storytelling. People came – the elders, the youngsters and the in-betweeners – to tell stories, to listen, to reminisce, to mingle, chat and eat.”

With Storybox, the intergenerational storytelling takes the form of a written story or a recorded oral narrative, whereas with Historypin it’s physical artefacts with explanations or contextualisation. “People are not necessarily having conversations in effective ways, just because of mass cultural differences or differences in training, so it becomes difficult to tell a cogent story between generations and between geolocations. This is what Storybox wanted to solve. It’s a gamified version of a basic storytelling structure: it shows how long you should listen, how long you should speak and what you should speak about. And this was a necessary precursor to being able to digitise the story onto a geolocated map.”

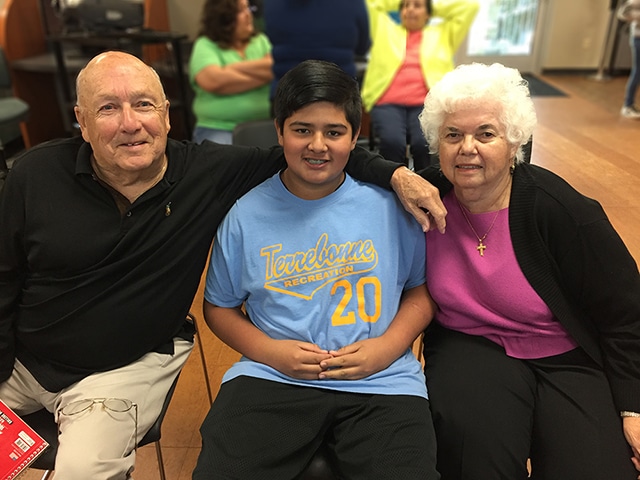

A heartwarming example is the Storybox party in Dulac, Louisiana, which drew people from across the age spectrum to celebrate the culture and history of their remote town. Photographs were used to trigger memories and act as catalysts for storytelling, and pre-printed invitations were given to children, so they could invite adults whose stories they were most curious about. And there was no sugarcoating. “Participants broached tough subjects, but mostly to acknowledge that there was a dark underbelly to some of the sunny, nostalgic themes. Race and ethnicity, as was the case elsewhere in America, historically determined how people were treated in this bayou town.”

Thirteen-year-old Alex Amaro invited his neighbours, Bernard Collins and Faith LeBoeuf, to a Storybox party:

Meanwhile, in Colombia, Comparte tu Rollo saw Historypin collaborate with the National Library of Colombia to increase the use of information technology through public libraries – engaging the whole country in storytelling to advance the peace process.

“This project is crucial to understand the diversity of this country, its multiple cultures who have contributed to what we currently are so that we understand why we have been as we were, why we continue to be so, and what we want to be.” – Consuelo Gaitán, Director of the National Library of Colombia

Historypin wants to make room for more cultural heritage work in organisations that primarily document the generations of marginalised people and communities – including people who identify as LGBT+, Indigenous people, African Americans, Latinx, immigrants, and victims of police violence and incarceration. The Shift US team also researches sustainable funding models for community-based archives through Architecting Sustainable Futures, as these institutions hold some of the most valuable materials documenting the lives of marginalised people.

Next, they are working on finding out how ‘pinning’ can turn into longer and more meaningful interactions. “We want to make the paths and possibilities more explicit and give people inspiration about what they can do, how they can use the site and apply it to their life.”

Together we can preserve history and create the change you want to see in your community.

AtlasAction: Want to run a Storybox event? Check out this free community toolkit. And watch the video below to learn how to start pinning.

Project leader

Hali Dardar, Partnerships Manager

Partners

This project has been selected as part of AgeFutures, a new storytelling project that maps the innovations transforming the lives of older people, and the designers, entrepreneurs and community leaders – across all generations – behind them. Atlas of the Future is excited to partner with Independent Age.

Support the Atlas

We want the Atlas of the Future media platform and our event to be available to everybody, everywhere for free – always. Fancy helping us spread stories of hope and optimism to create a better tomorrow? For those able, we'd be grateful for any donation.

- Please support the Atlas here

- Thank you!