United Kingdom (London)

We have taken, for the first time in human history, steps towards being able to change who we are at a fundamental level. On 1 February 2015, the UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) made this weighty and controversial decision, and for all the right reasons.

The government body approved an application by developmental biologist Kathy Niakan at the Francis Crick Institute of London to use a technique called CRISPR-Cas9 to study the development of donated human embryos – which will be destroyed after seven days, and not used for implantation. Niakan hopes that the study can determine how embryos develop in a healthy baby, leading to advancement in IVF: “The reason why it is so important is because miscarriages and infertility are extremely common,” she says, “but they’re not very well understood”.

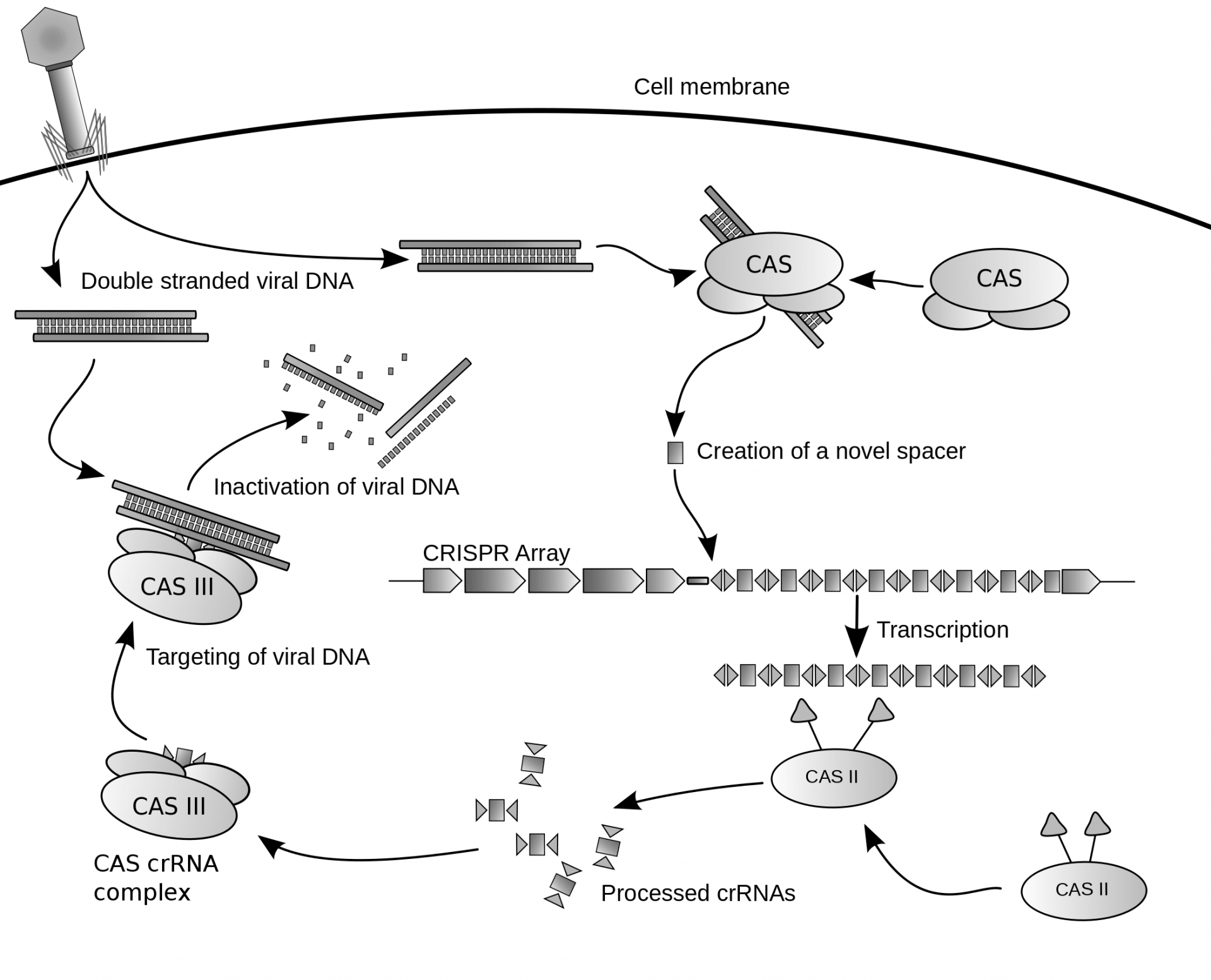

CRISPR-Cas9, the much-needed acronym of ‘Clustered Regularly-Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats’, and its associated protein, is a chemical which allows researchers to cut, move and replace parts of a gene sequence – the bits of your DNA that give you blonde hair or brown eyes – at a relatively low cost.

Where it really comes in useful is in the destroying of viruses. Bacteria are still susceptible to invasion by viruses, and CRISPR destroys unwanted guests by cutting its genome to prevent it from replicating. CRISPR’s ‘clusters’ are a collection of bases, the building blocks of DNA, with an immune response unlike our own. The ‘spaces’ between these clusters are the DNA remains of the virus, which many scientists believe provides a genetic memory of the virus and possibly an immunity to it.

Scientists are euphoric with this technique. By studying the human genome in much greater detail, they can determine how illnesses such as cancer develop. It might even prompt an end to the need for antibiotics, as our bodies are supplied with an immune system ready to combat infection and disease. Beyond ourselves, CRISPR could help to create more efficient biofuels or genetically alter crops for difficult climates as far afield as Mars.

Research such as this always goes hand-in-hand with controversy, no matter how honest intentions, and many will be asking the ‘designer babies’ question. Now that it is possible to alter the human genome, what’s to stop us eventually cutting out the bits we don’t want and adding in the bits we do? Restrictions in the UK make that very unlikely, which is one of the reasons that Niakan has been given the go-ahead. Not every country has such strict regulations however, and we will need to be alert to the ethical challenges that such technologies present us.

AtlasAction: Learn more about the precise power of the CRISPR-Cas9 system and the exciting yet controversial opportunities for genetic and epigenetic editing.

Bio

A chemistry graduate with an adoration of the outside world and an aversion to labs.

Project leader

Kathy Niakan, Francis Crick Institute

Support the Atlas

We want the Atlas of the Future media platform and our event to be available to everybody, everywhere for free – always. Fancy helping us spread stories of hope and optimism to create a better tomorrow? For those able, we'd be grateful for any donation.

- Please support the Atlas here

- Thank you!