In the sprawling high plains of the Free State province of South Africa, Conchita Milburn is playing a key part in freshwater aquaculture projects – sharing knowledge and implementing sustainable practices.

Aquaculture is exactly what it sounds like – farming fish, crustaceans, molluscs, aquatic plants, algae and other organisms – under controlled conditions. Combined with agriculture, it improves livelihoods, as well as alleviating food shortages for small-scale farmers.

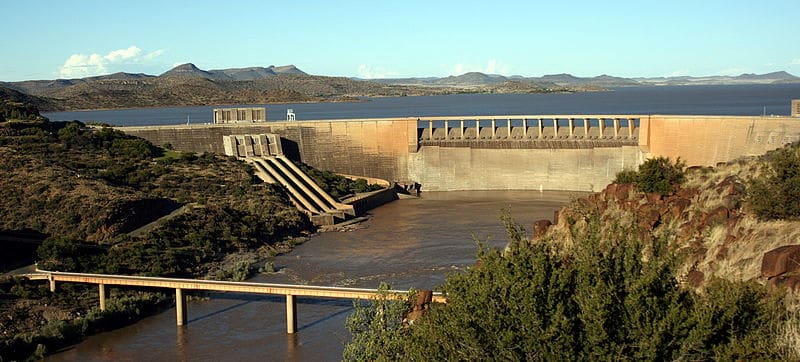

As head of the Gariep Dam Hatchery, a government hatchery and aquaculture demonstration centre that aims to develop sustainable practices, Conchita assists and supports emerging farmers.

We talked to the aquaculture mentor about sustainable fish farming, being a woman in a fishy world – and why catfish are hardcore.

Harvesting tilapia

Conchita Milburn:

I am an only child, and grew up watching National Geographic and Sir David Attenborough documentaries. I grew up inland and spent hours on end pretending to snorkel and dive in our swimming pool, imagining fantastical marine creatures all around me.

I always wanted to be a marine biologist. I was invited to tour an aquaculture facility and felt very comfortable in the environment, excited and interested in what I had seen. My enthusiasm led to a job offer.

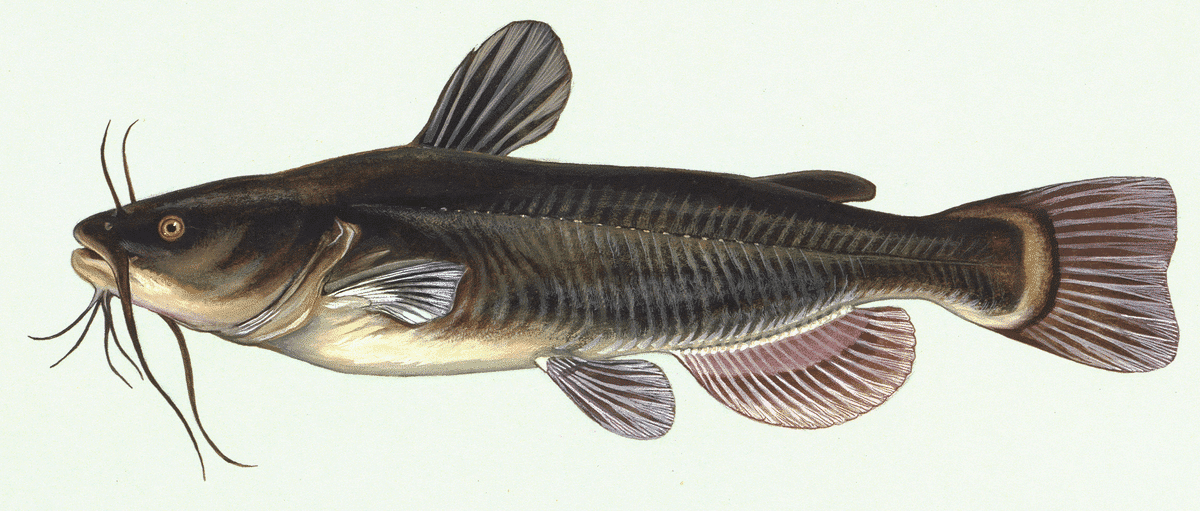

My first aquaculture job began when I managed a tilapia farm in Vilanculos, Mozambique. It was 2011 and our focus was on high-quality fingerling production (juvenile fish). Living and working in Mozambique for two years was an incredible experience. I went on to manage an African catfish farm in the small town of Graaff Reinet in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. It was there that I officially started teaching aquaculture.

It’s inspirational to see my trainees, mainly women from poor communities, become competent fish farmers. Many of them are the only breadwinners in their households.

Aquaculture trainees in South Africa

Aquaculture production offers many daily challenges, so it’s good that I enjoy problem-solving. I really enjoy the breeding component of aquaculture, and continually strive to improve survival rates within the hatchery.

We have a breeding schedule for tilapia, carp, catfish and ornamental fish like koi and goldfish, so I need to ensure that the broodstock (mature fish used for breeding) have been conditioned and selected, and eggs artificially spawned, selected or harvested.

Fish need permits. This is for when they are introduced to the hatchery and for provincial emerging farmers. I manage project planning, training and support services for those farmers.

Young catfish

The most unusual experience I’ve had is… performing experiments to determine the most humane method of killing catfish when harvesting – by running a current through the fish. Catfish are hardy and recuperate shortly after being stunned. Eventually we discovered that clove oil kills them humanely. Experimenting with electricity is quite nerve-wracking!

Our country is experiencing water shortages, so it’s extremely important to ensure that effluent water from the tanks is reused. We operate with a recirculating aquaculture system, which maximises water usage. We also make sure that the hatchery prevents any escapees, in our case, Nile tilapia, carp and catfish, by screening outlets as well as having a retention dam.

Gariep Dam is the biggest dam in South Africa and attracts fishing enthusiasts

I need to keep up to date with trends and innovations. Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) and offshore aquaculture have the most potential to change aquaculture because both have smaller environmental footprints.

Recirculating aquaculture systems can be used for aquaponics. The water used is circulated around the system from the fish tanks, through a series of filters and back to the fish tanks. Nutrients and wastes from the culture system are contained, and therefore do not have a negative impact on the surrounding environment, as flow through systems would have. The footprint of RAS is smaller, and water as well as energy used to heat the water is also conserved.

Offshore aquaculture has huge potential for the future. It involves fish being cultured in large submerged offshore structures that can even be remotely controlled to move to new locations. This system alleviates the environmental pollution caused by overloading the environment with nutrients, which occurs with inshore farming; opens up sheltered inland bays once again for recreational use; allows ecosystems to be revitalised, and bays can return to their natural beauty.

Free range farming by Aquapod

The biggest threat to sustainable fish farming is the spread of diseases. White Spot Syndrome (WSS) in shrimp, and Tilapia Lake Virus (TLV) are on the rise as species are exported and imported around the world. Pathogens and disease also increasing as stocking densities are increased in intensive farming. The use of antibiotics in aquaculture remains a concern, as well as the use of fishmeal in feed.

I analyse sustainability issues such as alternatives to fishmeal in feed. I am currently looking at supplementing our feed with MagMeal, which is produced from black soldier fly maggots, instead of fishmeal.

Fishmeal-free fish feed is good. Using fish as an ingredient in fishmeal is putting pressure on an already overexploited resource. These small fish sustain other fish, seabirds, marine mammals and contribute to human consumption. There are many exciting alternatives being researched and developed, such as using microalgae, insect-larvae, and microbial ingredients as alternatives.

The aquaculture industry’s greatest accomplishment is a reduction in the FIFO ratio (Fish in, Fish out). This is how much fishmeal is required per kilogram of fish produced, in terms of salmon farming, as well as the research and development in using fishmeal-free feed alternatives.

Spawning results

My dream position would be to work for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. It shares aquaculture knowledge with the world and provides emerging farmers with the tools that they need to get started. It develops sustainable fish farming globally, to aid in alleviating food shortages and poverty. I do believe that this is an attainable goal.

There can be challenges as a woman in aquaculture. When one contract was coming to an end, I applied for another job but my employer at the time told me that aquaculture is a male-dominated industry so I shouldn’t get my hopes up too much. I got the job.

I believe women are empowering one another a lot more. Women are addressing inequalities and there has been an improvement. I know of quite a few women with government positions in aquaculture. In many poor communities, funding is now being made available for training and most applicants are women.

See yourself as an equal. Study hard and work hard. Do not stand back, believing that some work should be left to the men. Get involved all round. Spend time learning and developing your knowledge and skills in areas that you are not too familiar or comfortable with. You need to be an all-rounder – that includes a bit of engineering, getting dirty and wet and carrying bags of feed.

I draw hope from acts of kindness; from those that give back to others, and commit to being the custodians of the planet and its inhabitants, and from nature.

My FutureHero power would be… to fly around the world zapping all the plastic debris in the oceans to smithereens (without creating greenhouse gases). The harm that we are causing to the marine world through plastic pollution is heartbreaking.

FIN

This feature was adapted from a piece by Bonnie Waycott for The Fish Site, a freelance writer specialising in Japan’s aquaculture.